My brother stalked his way meticulously up the West Virginia power line right of way, his Winchester Featherweight at low ready.

The crisp Thanksgiving wind swirled and nipped playfully at my ears as I trailed my brother up the steep hill, ready to lend fire support in case there were more deer than the one whitetail buck my father had sent us after. We'd been chasing these deer for a week, and were getting to know their patterns. We were ready to put some venison in the freezer.

A cacophony of breaking twigs and rustling oak leaves shattered the air, and with a flash of a snowy white tail and the gleam of sunlight on fast-moving antlers, the buck erupted from his bed and charged into the adjoining woods, 30 yards away. When the dust settled and our hearts stopped trying to hammer their ways out of our respective chests, my brother motioned for me to stay on the power line to cover any circling tactics by the deer. He made his way silently up the hill a hundred yards, then cut in the woods after the wary buck.

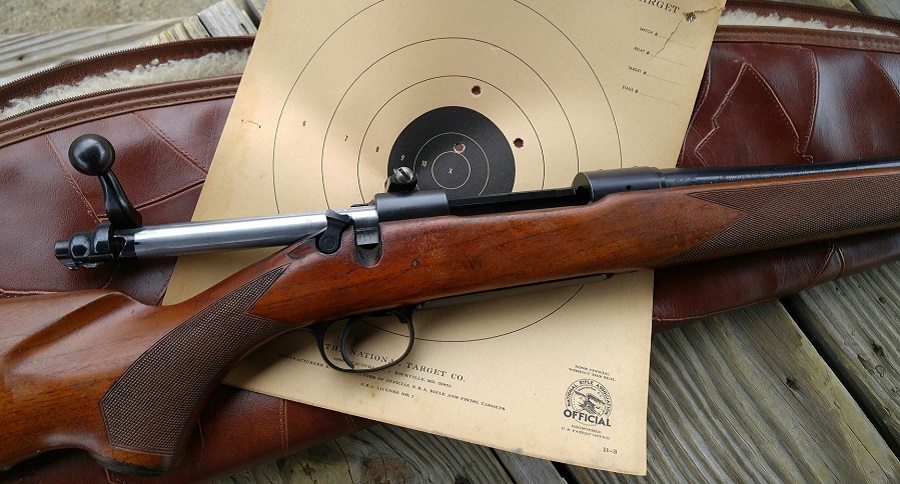

I looped my arm through the oil-stained leather military sling on my beloved old Winchester 54, and turned to watch the gully below me, rifle at the ready. I didn't have to wait long.

The gray antlered freight train fairly exploded out of the woods from my left, hellbent on escaping the orange-clad intruder behind him. The big Winchester bolt gun came to my shoulder as sweetly as a lover's embrace. The Buehler safety snicked off crisply, and the Lyman 48's aperture centered the bright brass bead of the front sight as it had done for me hundreds of times before. The iron sights aligned on the fast-moving ungulate's shoulder 120 yards away, and the Winchester boomed out three times across the West Virginia hillside. Two of the Federal 180-grain .30-06 rounds found their mark, and the buck staggered against a tree and fell, kicking briefly before expiring, its heart shot to pieces. The 90-year-old Winchester had again proved the point it had made many times before - old guns and iron sights still work, and they work well.

Your author enjoying an iron-sighted Winchester Model 54 in .22 Hornet.

The above narrative really happened; I was fortunate enough to make a (I thought) remarkable shot on a whitetail buck running at full tilt, a healthy distance away. I'll be 100% honest: if I didn't have the rifle I did with the sights it had, I may not have ever bagged that buck, or maybe only gotten one round off. The Lyman 48 aperture rear sight and Marble's brass bead front sight worked in perfect concert to help me get three quick rounds off with a bolt-action .30-06 (my father said it was the first time he'd ever heard a bolt action go full auto), and connect twice - right in the buck's boiler room.

What are "Iron Sights"?

For the purposes of this article, we're going to use the term "iron sights" to include any firearm-mounted alignment devices that aren't optics - buckhorn sights, notch sights, aperture/peep/receiver sights, ghost ring sights, tang sights, express sights, as well as anything that falls under the wide array of non-magnified sighting devices known as "BUIS" (Back Up Iron Sights) in the modern sporting rifle world. Despite the term, most "iron" sights are crafted of steel, aluminum, or polymer.

A sporterized Krag carbine makes wonderful use of a sturdy (and valuable!) Redfield receiver sight.

These days, red dot sights and low-magnification optics have become the sighting method of choice for close-in, fast action on moving targets. However, for over a century, (before battery-powered dot sights were ever thought of), the aperture iron sight ruled the roost in the sighting world. Yes, scopes were available to the rifleman even back in the U.S. Civil War days, but they were long, ponderous, immensely delicate, and expensive.

Instead, most soldiers, buffalo hunters, sharp shooters, trick shots and everyday sportsmen utilized the Mark 1 eyeball and standard metallic sights to put the bullet where it was needed. If you've seen Tom Selleck in the fantastic movie "Quigley Down Under", you've seen vernier tang-mounted aperture iron sights in action.

Alternatives to Iron Sights

Since the 1960s (or maybe even a touch before), telescopic sights have been slowly taking over the mainstream sighting arrangements for hunters and military purposes. The need to use iron sights on guns dictated early firearms design, with low stock combs and factory-added drilled and tapped holes or dovetails for mounting sights. As the scope has evolved, so too have modern rifle designs - "Monte Carlo" stocks and raised cheekpieces were needed to get the shooter's head up to see through the lenses properly. Integral scope bases and Picatinny rails now have sprouted on firearms to accept any manner of optic the user can dream up and afford. Handgun platforms haven't been left in the dust to stagnate either; pistol slides are frequently milled out to accept miniature red dots. Revolvers have accommodations for aftermarket scope mounts. Iron sights on AR-15s have disappeared from the fixed "carrying handle" type A1/A2 setups to being mounted on rails. The balance is certainly tipped towards favoring optics in lieu of fixed iron sights.

This buck fell to an iron-sighted Marlin 336EER in .356 Winchester.

And why shouldn't it? Modern optics are robust, reliable, brilliantly clear, and scopes provide magnification for that reaching-out-and-touching we all need to do occasionally. Red dots and low-magnification scopes allow fast, precise target acquisition and quick follow-up shots. Optics can certainly help crutch a mediocre shooter and help them become a better marksman. If one is aged and the ol' peepers don't work as well as they used to, optics will help your target and sighting system clarity to help you do what you love for a longer period of time.

...but, are iron sights obsolete?

Not remotely! Granted, they are zero-magnification sighting devices, but as long as you can see your target well enough to place a bullet with precision, iron sights still work as well as they did a century ago; that hasn't changed. Ask any member of our military who has gone through basic rifle training, and they will tell you they were able to hit targets hundreds of meters away with open sights. Open sights are definitely still a viable sighting option.

Picture via Wikimedia Commons.

As a matter of fact, while my eyes are still (relatively) young, I still vastly prefer a good solid Lyman or Redfield receiver sight on most of my hunting rifles. "Why?" you may ask. "Why, Drew, are you so thickheaded as to limit yourself when so many fine optics are available?"

My response is twofold: first, my father trained me from a young age to use aperture sights, and I have grown quite familiar, practiced and confident with them. As a matter of fact, even on my rifles that do utilize optics, I still try to ensure that I use quick detachable mounts for the scope. This allows me to use iron sights as a backup, similar in concept to the military use of iron sights on an AR-15 for backup purposes to optics. I've used iron sights for a long time, and they work very well for me.

A Savage 99 Carbine and a Winchester 1895 Carbine both use Lyman receiver sights to make great Maine deer rifles.

Secondly, I dearly love to carry rifles with no optics in the woods. I don't use a sling much - I like to have the rifle in my hands in case I'm fortunate enough to see game. With no errant scopes and mounting hardware to get in the way, rifles carry like a dream in my hands - especially bolt action rifles, believe it or not. So unless I'm sitting in a stand or in an area where I can shoot over 150 yards, it's iron sights for me!

...and while I can't speak for you, I can tell you that iron sights, especially good "peep" aperture or ghost ring setups, are a great upgrade to your rifle, and can help you become a better shooter. They're fast to use, intuitive to use, inexpensive compared to optics, rugged as hell, and low-profile. Perhaps best of all, they're reliable, no battery powered, and immune to condensation and leaking. What's not to like about about any of that? Next time you're perusing the rack at a gun shop, don't look down your nose at a gun with iron sights; give it a whirl and you may be happily surprised!

All images courtesy of Drew Perez unless otherwise stated.