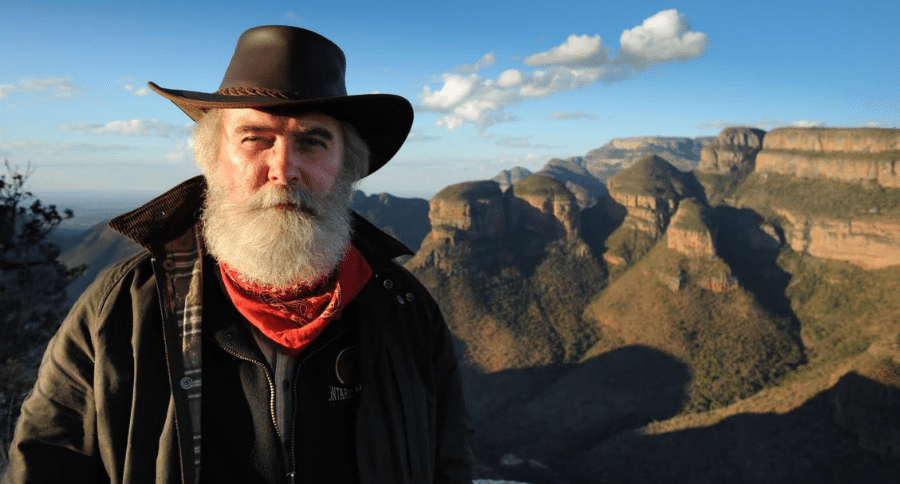

Celebrated conservationist Shane Mahoney continues his fascinating discussion with Wide Open Spaces on conservation and the hunting world.

In this installment of our exclusive interview with noted conservationist Shane Mahoney, Shane discusses the message of conservation and how we need to tailor it to a new, oftentimes distant and disconnected public. We also talk about the history of the hunting message and how it has fallen short or misses the mark of reaching a modern public.

We talk about the anti-hunting community and their ignorance of hunting as conservation, and how the hunting community may be partly to blame for that ignorance. We also talk about William Shatner and a vegan Shane once met.

To read Part I of our exclusive interview with Shane Mahoney, CLICK HERE.

For Part II, CLICK HERE.

For Part III, CLICK HERE.

DAVID SMITH: Getting the conservation message out to people is the key. There may be, for example, a rancher who also is a contributor to the RMEF and to the Clean Water Initiative, but he just doesn't get the message out or herald his involvement with these other programs. He does it quietly. We need to get the message out to the non-hunter as well.

SHANE MAHONEY: I've long advocated that we need to place conservation foremost in our messages. And that sounds like, "Of course! We should." But we aren't. I know we weren't. I've been involved in print and television and lecturing for a quarter of a century in the United States of America and Canada on these issues, and I know we were not putting conservation first. What happened with the hunting and angling industry to an extent is that up until about the 1960s or so, this was all just taken for granted. You know, we hunted, we fished, we came out of rural societies, many of us still lived in rural communities, or more of us did, or our parents did. There was this much, much deeper connection.

So it was just taken for granted. When we began to see the big marriage between industry, the hunting industry, so to speak, and hunting and angling, we began to generate quite different messaging.

First we didn't really have much messaging because we talked to ourselves, and most of society thought hunting and angling was just a way of life and it was just accepted. Then when we started to produce messaging it became very commercialized. We all know this is true, This is not a slight on anyone. It's the way the ideas and processes evolved. The messaging was about de-emphasizing the animal, emphasizing the hunter, de-emphasizing the hunt, and emphasizing the kill. We all know this is true. People can be upset with these comments if they want. But we all know this is true.

If you look up the literature in the 1900s, 1920s, 1930s, 1940s, the Jack O'Connor kind of stuff, you know, all the people who wrote, the Roosevelts and so on. This is what was explored. The amazing experience of the hunt, the hardship, the storms that came and the incredible capacities of the animal to avoid, to always move out of reach, and so on and so forth.

If they did take an arrow, it wasn't because he was such a great human being, it was because good fortune had kind of smiled on him. And it was completely different. And so we started to replace all of that with an emphasis on the kill. Look at our television shows. A lot of people spoke about it, realized it. And most hunters don't watch them anyway.

I don't want to be hypercritical here because there are some very good shows out there. But a lot of them emphasize this kill-kind-of-syndrome, and as a result of that - partly, there are other reasons in society - lots of people began to wonder about this hunting thing. Is this all just about the hunter? Is it all just about big money? Is it all just about ego? Is it really about conservation?

Those questions started to embed themselves in the public mind, and that's why we're seeing the challenges, and of course they grew. Like little seeds, they grew and grew and grew and grew, until they had more of an impact, more of a presence. And that's why we're seeing some of the challenges that we see to hunting and to a lesser extent to angling today. Certainly globally, there was a huge backlash against hunting.

Theodore Roosevelt via Corbis (Getty)

SMITH: Well, I would say that you have been fairly instrumental in turning that around a bit. I recently did a brief article on old, vintage firearm ads, and some of the marketing techniques were exactly what you're speaking of. It was all about the kill and an emphasis on the hunter.

But now "Hunting Is Conservation", as the RMEF says. I mean, that is out there all the time. We're seeing hunting shows by, say, Remi Warren or whoever, where they don't even harvest an animal. They go through the whole show and they may not even harvest an animal. It's about the experience and about the animal. Those are, I would say, few and far between in the grand scheme, but they are gaining more attention. But as we humans often do, we often react to something and go hard in the opposite direction.

MAHONEY: Yeah, I think you're right. And I'm very encouraged. People would always agree, but they wouldn't act on it. But now I think what's happened is that practical realities are convincing us that the future in this arena is going to be profitable. To be successful, they're going to have to shift. And what I think is influencing this is the aging of the hunting public.

Now whether we want to admit it or not our feelings and attitudes and ways of thinking change as we mature. The young man does not think the same as the teenager, and the young man or woman does not think the same as the middle-aged man or woman, and the middle-aged man or woman does not think the same as the older man or woman, you know what I mean? We change over our lifetimes. And this huge bulge that's in the hunting community that's, say, between 50 and 75, let's just put those parameters on it. They have different attitudes than they had when they were 20 and when they were 25.

So you're also getting the influence from within. People are beginning to realize, it is more about the experience. And it is more about the animal. I firmly believe that the trajectory we took from the 1960s and 1970s until fairly recently did us a lot of harm. And it's a lot of harm that we now have to correct. So when you see organizations talk about conservation more, and television shows and conventions and so on and so forth, it's a good start, but we need to go a lot further, and we need to go a lot further a lot faster. Because the challenges are real.

I don't think that hunting in the United States and Canada is in peril, don't get me wrong. But certain kinds of hunting, they are being heavily challenged.

Ernest Hemingway, 1934, via Wikimedia Commons

SMITH: Well, some aspects of it are getting chipped away. The anti-hunting movement, if you can call it that, has a very loud and very powerful voice.

MAHONEY: It does.

SMITH: I remember something I saw when I was a kid. It was back during the old American Sportsman television show. I remember William Shatner - they used to have celebrities go on and fish and hunt - and he was on a bear hunt. And I believe he was on the show more than once. But on this bear hunt he killed a bear. And after that he kind of disappeared from the hunting scene. And then some years later I read that he had an experience on that show.

He was an avid hunter, and when the time came for the film crew to film him shooting the bear - I think he was hunting with a bow and arrow - and he said in a later book or something that he was pressured into getting the kill, and all that mattered to the film crew was filming him getting the kill. And he became so turned off by that, that he completely gave up hunting. And it just struck me as what a sad moment, that that experience and that emphasis on the kill, and not the hunting experience would turn a man from being a hunter to being almost an anti-hunter.

MAHONEY: That's a tremendous story. Thank you for sharing it, because I wasn't aware of that at all. But it's a very powerful example of what we're talking about.

You know, the world is changing everywhere. Whether we're talking young Chinese, young Vietnamese, young Russians, young Americans, young Germans...it doesn't matter...but the world is a very interconnected place. And the communications systems we have today ensure that it's inevitable that it will always be so now. And attitudes are flowing across borders, just as people do. And of course attitudes flow across borders even when people don't move, because of the communications systems we have today. And so, the hunting world needs to understand - and I can't emphasize this enough - the hunting world needs to understand that the message is not for us.

The person who has experienced hunting or angling, you know, who's had the thrill and the excitement, and the natural experience that in many cases have nothing to do with taking an animal. Simply being out there in nature. Seeing things that you would never see if you weren't hunting. Because you wouldn't be putting yourself in the wild circumstances where you are.

You wouldn't be up there in a tree in the morning when the day breaks open. You wouldn't be coming back in the long shadows of the evening, bone tired, and all of a sudden you turn the corner and there's a huge bull moose standing twenty meters away from you. I mean, those experiences don't happen unless you're making a determined effort to put yourself in those circumstances.

So, we get it. We get it. The people who have that experience, they know all the subtlety and nuance about it. But the people who have never experienced it, how in the name of goodness can we expect them to understand implicitly? And the hunting community often gets frustrated over people who are anti-hunting. "They don't understand. We do this. We do that. We do the other thing." Well of course they don't understand! That's the point! They don't understand. And we're part of the problem!

You know, are Martians going to come down, lower the ramp, get out their pamphlets and say to the anti-hunters, "Read this. Hunters saved your wildlife!" We need to define a new modern dialogue with a modern public.

Now, I'll give you an example. Let's take hunter retention and recruitment programs. When we began to realize that a problem was coming our way twenty-odd years ago now, we determined that we needed to launch what we call hunter retention and recruitment, and be engaged in these programs and so forth. And I helped launch some of them. I was there in some cases at the very first meetings to help colleagues and friends launch these. So, the idea of doing something was, of course, important. But think carefully about what we did.

We created programs where we wanted to make it easier for youth to become engaged, where we wanted hunters to take young people out and show them hunting. We knew that the family circumstances changed a lot in American society and Canadian society. We wanted to have these special youth hunts, these special days. It was all about trying to bring young men and young women, girls and boys, into this activity.

But we did it in a way that mirrored our experiences in our childhoods. Where Uncle Jack took me out or my father took me out, or I went hunting with my cousins all the time. We were trying to recreate a world that had long, long changed.

We see who's coming into hunting. Women, ages 25 and 40 mostly, but not exclusively. Significantly influenced by the desire to have good food, and concerned about food for their children. And women are concerned, obviously mothers are very, very concerned about this.

And these young males, often coming out of urban centers, who have absolutely no history with hunting whatsoever. And who have no family member who do it, who have no kind of experience, but do it for their own current, cultural reasons now.

They want to take responsibility for the planet. They want to take responsibility for their food. They're very concerned about animal welfare. They're very concerned about the loss of wild places. Not in necessarily the same way that we have been or are. And so, we ended up spending millions and millions and millions of dollars collectively, trying to develop programs that were influenced by our memories.

How many times have people said to me, "I used to go to school with my shotgun across the handlebars of my bike." Or "When I went to Starbucks I'd bring my .22 and nobody said a word." Beautiful. Lovely. Just like my childhood in rural Newfoundland was like something out of a fairy tale. And it was, believe me. But it's gone. It's gone. And it's not coming back. And so what we have to do is find a modern narrative for a modern public, and I firmly believe that we can do this.

I firmly believe that the experience in nature, the fact that you are assisting in the conservation of wildlife, and the fact that you can obtain for you and your family wild, organic, the best food possible to harvest. You can do it for fish and game, you can do it with berries and wild mushrooms and wild fruits and on and on and on.

That you can, even in 21st century America, with all the changes that have taken place since Teddy Roosevelt's time, and all the changes that have taken place in Canada since Sir Wilfrid Laurier's time, my Prime Minister who joined with Roosevelt to help launch the North American Model.

Despite all those changes, we can still do this. It's amazing. And it's open to anyone, anyone. Any race, any color, any religion. All you have to be is a citizen, train yourself to be proficient, acquire a permit or a license, and then the opportunity is there for you. And we know that any hunter will be more than happy to give guidance.

I spoke at a radio interview in Michigan about two years ago. I was just starting to talk about this idea of my Wild Harvest project. And I was on a break with the host of the radio show, and I was at the soundboard outside, a soundproof booth, with a young woman, probably 25 years of age. And I talked about veganism, and I talked about not eating meat, and I talked about the value of wild meat. I covered a lot of ground. So I came out and the young lady came up and she said, "Mr. Mahoney, I'd like to introduce myself" - I can't recall her name - but she said, "I'm a vegan." And she said, "My husband is a vegan."

That's a good view, because as I said in the show, the people that really commit themselves to that lifestyle, that takes a big commitment. And you can be healthy, obviously, on those diets. It just means that you've got to really know what you're doing. And I admire people who make that commitment, I totally do.

And so she said to me, "The reason I'm a vegan, and the reason my husband is a vegan, is that it's a healthy lifestyle" - and it certainly can be; we all need to eat more fruits and vegetables, every medical doctor in the world will tell us that, so there's no doubt it's healthy - and so she said, "The other reason we did it is because we thought we were doing the right thing in protecting wildlife. We just don't want to see animals killed for our food."

One of the points I made in that interview was, look, we have to make a choice, obviously, about our foods. And one of the things we have to decide is when are the natural systems natural, or will we continue to take natural systems and modify them extensively? So if the whole world wants to feed on agricultural production you know we're going to have to eventually take some other additional percentage of wildlife habitat out of existence, and turn it over to those kinds of productions.

Furthermore, if we don't find a utility to some extent for wild creatures - and this is playing out in Africa especially - if they don't have some real value to us, we kind of forget about them. We don't want them, we don't miss them anymore.

And so I was speaking that night - this is an absolutely true story - at the Northeast Michigan Chapter of Safari Club International, at their annual event. I spoke at a high school at the same time, did the radio interviews, and so on. And she asked me if she could attend the Safari Club International event. I said, well, I can't really speak for the organizers, but I'm sure they would be delighted. You just come, and you'll probably have to buy a ticket and all that kind of thing.

But, after I spoke that night at the Safari Club International Convention I was coming out of the doors of the room, of the ballroom where they had their auctions and serve the dinner and all that, and there she was. Her and her husband. They were just coming back in. They had bought a drink outside where the bar was set up. And she was just walking back into the room.

So, she was there because, obviously, food was very important to her. Obviously she made this very rigorous shift to becoming a full vegan. And so did her husband. They were two wonderfully healthy-looking human beings. And here they were at a Safari Club International event, wondering about all this stuff about hunting. But the key was food.

Now, if we could convince her... A lot of people say "I could never hunt. I don't ever hunt," I say look, you don't have to. Find a hunter, really, reach out to somebody and just ask them if they have any meat. I guarantee you 99.9 percent of those hunters will share.

Especially if you want to trade something. I don't know, maybe you're a photographer. Give them a photo. Maybe, I don't know, maybe you knit things. Give them something knitted. Set up that relationship with hunters and you will have game meat for as long as that individual hunts and is able to give you some.

SMITH: That's wonderful.

MAHONEY: Yeah! This is how we change. You know, I don't want hunting and angling to be elevated. This is what so many of my colleagues and so many in the hunting world seem to be striving for. For it to be better recognized and for it to be elevated in some sort of way. I don't want that at all.

I want hunting and angling to "disappear" into the fabric of American and Canadian life again. I don't want it to be a target. I just want it to be, you know:

"I have a neighbor who grows his own fruit."

Hey, that's great.

"I have a neighbor who berry picks."

You know that's amazing.

"I have a neighbor who goes out and catches some codfish."

That's wonderful.

"I have a neighbor who gets a moose every year."

That's great.

And it just goes on from there with no more hesitancy, no more special kinds of attention at all.

Like what you see here? You can read more great articles by David Smith at his facebook page, Stumpjack Outdoors.

NEXT: Should We Trade Rhino Horn to Save the Species?