Invasive species are infiltrating nearly every corner of the United States, crawling, squirming, jumping, flying, and swimming into our ecosystems. These non-native invaders, which are often introduced unintentionally or accidentally, can disrupt the balance of natural habitats, outcompete native species, and introduce new diseases. While some invasive species such as feral hogs, the Asian long-horned beetle, and the emerald ash borer have been widely publicized, others have managed to slip under the radar. Despite their lower profile, these lesser-known invasive species can cause just as much damage as their more famous counterparts.

Unraveling the impact of invasive species is not just about understanding their effects on biodiversity and ecosystems but also addressing their consequences for human health, economies, and cultures. The damage they cause can be direct, through the destruction of habitat, or indirect, by triggering ripple effects through ecosystems. Moreover, invasive species can have serious economic impacts, leading to decreased agricultural productivity, costly eradication efforts, and increased management expenses for natural resources.

Many people may be surprised to learn that even species that seem harmless or beneficial can have negative impacts when introduced to new environments. For example, some introduced plants that are popular in landscaping can spread aggressively and choke out native plants, altering the entire makeup of local ecosystems.

As the pace of global trade and travel increases, so does the risk of invasive species introductions. Efforts to prevent their spread, manage their impacts, and protect native ecosystems are more crucial than ever. Here, we'll introduce you to five lesser-known invasive species that are becoming a serious problem in the United States. By understanding the threats these species pose and taking steps to mitigate their impacts, we can help protect our native ecosystems and the diverse life they support.

1. Argentine Black and White Tegu

Getty

The Argentine black and white tegu is a patterned lizard that is causing havoc throughout Georgia and beyond. It can grow up to 4 feet long and weigh more than 10 pounds. It's native to South America but not the American South.

Tegus are active during the daytime. They can be identified by their signature black and white coloration, which can include shades of gray, in a banded pattern on their backs and tails. Hatchlings have distinguishable bright green on their heads, but that coloration fades at once they reach about a month old.

They move fast on both ground and in water, and they can stay submerged for extended periods.

This scaly nuisance loves to raid nests of eggs. It eats the eggs of ground-nesting birds including quail and turkey, and other reptiles such as alligators and gopher tortoises (both of which are protected species).

There is also the nasty potential of tegus spreading exotic parasites to native wildlife.

2. Asian Jumping Worm

Susan Day, UW Madison Arboretum

Crazy worms, snake worms, Alabama jumpers—these pesky invasive worms are taking root in pockets all across the Midwest and Northeast.

Jumping worms look different from the common earthworms you might recognize in your garden. Jumping worms do just that—they jump around and thrash their bodies in a distinctive way. Another feature that makes them stand out is the white collar (or clitellum). It is smooth, milky-white, and located approximately one-third of the way down the length of the worm's body from its head.

These wiggly worms are actually a significant threat to forest habitats. They ruin soil quality, making it difficult for plants to take root. This in turn leads to reduced food source for native creatures such as white tail deer, rabbits, and others. Jumping worms devour the rich upper organic layer of nutrient-dense matter near the soil surface and leave behind a grainy soil full of worm castings that is robbed of any nutritional value. According to Colgate University biology professor Tim McCay, this alters the physical structure of the soil, turning it into something that resembles coffee grounds or boiled hamburger meat.

Jumping worms are asexual, or parthenogenetic, meaning they can produce eggs without the need for a mate. This means that even one wayward worm can start a new population. They also mature in only 60 days, so it does not take long for a cluster to be established in a location. The first hatch usually occurs in late June to early July. By September, a population can double. Adult jumping worms perish over the winter, but the larvae survive in microscopic cocoons in the soil or leaf litter. Those larvae hatch in late spring, and the cycle starts over again. A map of recorded establishments of jumping worms in the United States is available from iMapInvasives.

3. Northern Snakehead

Getty

The northern snakehead is a non-native fish and is distinguished from other fish by its unique ability to breathe air, which allows it to migrate short distances over land. It can even survive on land for up to four days. National Geographic called the species an insatiable predator with the potential to obliterate a native food chain. One was just found in Missouri waters, raising serious alarm bells.

They can be identified by their slithery, serpentine-like appearance, with a scaly head and eyes set near the top rather than the sides. Full-grown snakeheads can reach up to 5 feet in length.

Their detrimental presence has been confirmed in states across the nation including Pennsylvania, New Jersey, New Jersey, Louisiana, California, Delaware, Florida, Georgia, Hawaii, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Arkansas, Virginia, Rhode Island and, most recently, Missouri.

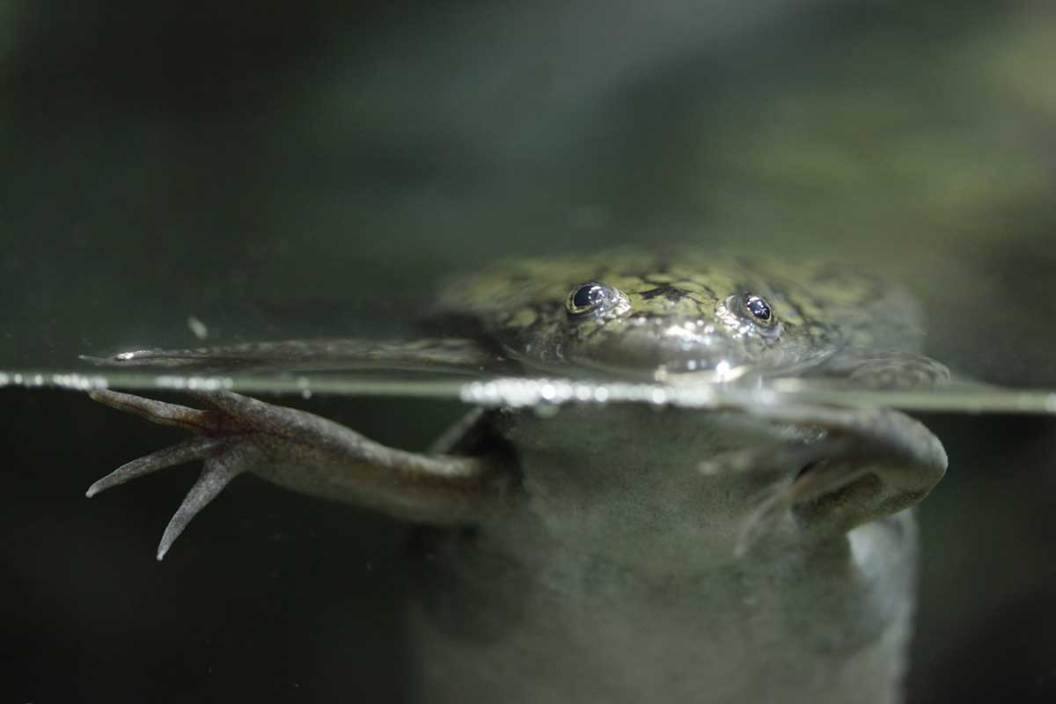

4. African Clawed Frog

A little frog with a big belly and black claws on its feet, the African clawed frog is an invasive amphibian that disrupts ecosystems and affects native populations, including trout and salmon.

African clawed frogs have voracious appetites and eat large amounts of native insects, fry, and tadpoles, according to Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife research scientist Max Lambert. When African clawed frogs enter a water system, they can quickly decimate native populations. Established infestations of these gluttonous frogs have been reported in many states, with concentrations in Washington, California, and Florida.

They also carry many diseases and, with that, the potential to introduce harmful pathogens into native ecosystems—which can destroy native amphibian and fish populations. They are such a known vector of disease that if African clawed frogs are discovered in a body of water, that water is then required to be quarantined because of the diseases they carry. Even people should take care when handling African clawed frogs. Those same diseases can transfer to humans and cause sickness. People should thoroughly wash their hands after any contact with an African clawed frog.

African clawed frogs are usually easy to distinguish from most native frogs. They have a patchy olive-to-brown skin coloring with no eyelids, tongues, or vocal sacs. The front feet are not webbed, but the back feet are fully webbed and have sharp, inky-black claws. Their tadpoles resemble small catfish, with long barbs extending from each side of the chin.

5. Chinese Mitten Crab

A quick walking crab with two big hairy claws—meet the mitten crab.

Easily identified by the unmistakable fur that covers their front claws, they have other distinctive features including a notch between the eyes with four spines along each side of the notch, and eight sharp and pointy legs.

In China, where mitten crabs are native, they considered a delicacy in many dishes. They are banned in the United States, but that does not stop the black-market sale and transport of these distinctive creatures.

Mitten crabs are ferocious eaters that prey on local wildlife, such as native fish populations. This not only threatens those fish populations but also the game animals that consume fish, such as waterfowl. They are a huge annoyance to fisheries. These crabs have become such a nuisance invasive species that they landed a spot on the list of the top 100 invasive species in the world.

These problematic crabs have already spread to several California waterways, the Connecticut shore, the Chesapeake and Delaware bays, and the Hudson River, according to the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center. They can migrate either on land or water up to 11 miles per day.

READ MORE: Invasive Chinese Mitten Crabs are Quietly Taking Over in New England