If someone told you they'd experienced time travel, you'd be dubious at best. But if you think about it, the majority of Americans do it every year, twice a year. That's right, we're arrived again at that magical time-shifting event: Daylight Savings Time.

Standard Time ends on March 10 at 2 a.m. for residents of 48 of the 50 states (the outliers: Hawaii and most of Arizona), when the clocks shift an hour forward. While most of us are asleep while it happens, many who enjoy an extra hour of light at the end of our day are thankful when that fateful day in March comes around and moves time forward (and rueful when it goes back come fall). Still, a lot of us wonder: Why do we have daylight savings time?

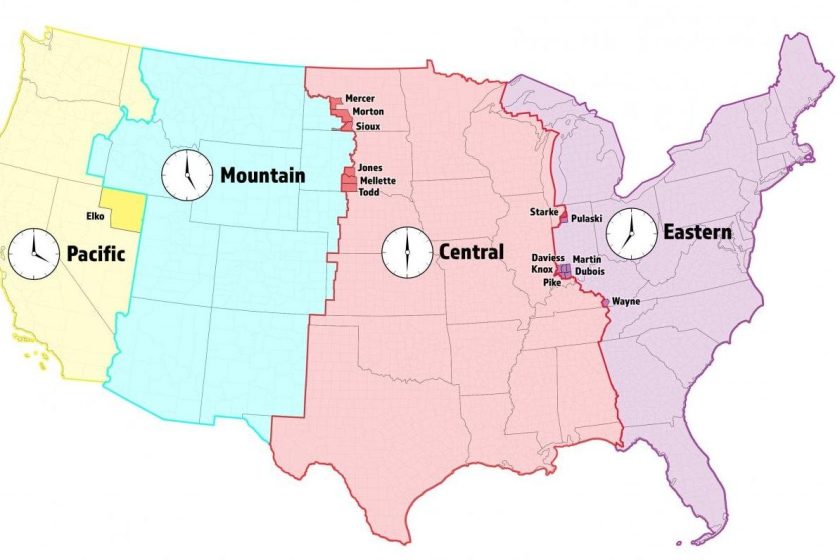

The answer is rooted in the history of, well, time itself. Prior to the 1880s, Americans calculated time based on the location of the sun, resulting in over 144 local times across North America—life at a slower pace simply didn't require clocks' precision when it took days to travel anywhere. Federally standardizing the time zones was the idea of the transcontinental railroad companies, with convenience and safety at its core. If arrival and departure timetables could be synchronized, it would make the trains easier to catch—and would minimize collisions on the track. In 1883, four zones were set across Canada in the U.S.: eastern, central, mountain, and Pacific. The Standard Time Act of 1918 officially confirmed these, plus one more time zone for Alaska. It also mandated Daylight Savings Time for one year to help conserve fuel during World War I, as had already been enacted as a wartime measure in Europe—not for the farmers, as is commonly believed.

After the daylight savings measure expired and the war ended, states that voted to follow it were permitted to do so at the local level. The current national standards were established in 1966 by the Department of Transportation with the Uniform Time Act, which established time zones for all of the U.S. and its possessions, as well as gave both Congress and the Secretary of Transportation oversight to change a time-zone boundary.

Since then, the dates and durations of Daylight Savings Time have been federally modified here and there, but the changing of the clocks has remained a constant, despite protestations from many Americans who would prefer sticking with one time scheme, whether it be Standard or Daylight. Proponents for Standard time's earlier sunrise advocate that it's better for golf course, ski resorts, and schoolchildren. Advocates for permanent Daylight time suggest the later sunsets are better for the economy and tourism. Pretty much everyone against the time change simply hate the flux of gaining and losing an hour of sleep and argues that staying put is better for human health and safety.

U.S. Department of Transportation

By federal law, no states are permitted to go on permanent DST (effectively, to change time zones) without approval of the Department of Transportation or congressional statute. In the last 20 years, 15 localities have successfully petitioned to change time zones—mostly specific counties within states that tend to do business with the neighboring state that is in a different time zone. In addition, at least 40 states have introduced legislation to propose altering their time in some form or other, either by proposing date changes to when Daylight Savings occurs, or by proposing moves to a neighboring time zone or to permanently stay on either Daylight or Standard time. Some states include contingencies based upon legislative changes of neighboring states; for example, Oregon would only move to permanent DST if Washington does.

But the reality is, nothing will happen without federal action. In 2022, we got close: The Sunshine Protection Act was passed by the Senate, which would set the entire U.S. on permanent Daylight Savings Time. However, the bill expired when there was no vote by the House of Representatives. It was reintroduced in 2023, but the new iteration has stalled out in both the Senate and the House.

For now, we'll continue this micro form of time travel, shifting the clocks an hour forward in the spring, only to fall back again come November.