As hunters, it's easy for us to point out conservation's great success stories. Animals like the wild turkey, the whitetail deer, and the pronghorn antelope all returned from the brink of extinction into the stable populations we all know, love, and hunt today. However, it's also worth looking back into the history of conservation in America, to see where we failed in protecting a species, and to see what lessons we can take away. Perhaps no other animal was failed more than the eastern subspecies of elk. There is some argument over whether it was a distinct subspecies or simply an entire population that was wiped out. Either way, these animals' former range once encompassed the entire Midwest.

There were massive elk herds living in Indiana, Ohio, Illinois, Iowa, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, and the Carolinas among other states. It may be hard to fathom elk once called these portions of the eastern United States home. Most either have none, or only a few hundred animals in modern times. Had they not been wiped out, the face of hunting in those states would be radically different than what most of us know today. This is the tragic story of what happened to this population of elk, and the conservation lessons we learned the hard way after wiping an entire subspecies off the face of the Earth forever.

Why Did the Eastern Elk Go Extinct?

Wikimedia Commons: John J. Audobon

The history of elk populations in the eastern part of the U.S. ties in directly with the birth of the Nation itself. Prior to European explorers, Native Americans did hunt for elk. However, there were not enough of them to make a massive dent in the populations, and elk continued to thrive for hundreds of years even after the first landings of explorers. As the population of America exploded, this influx of new mouths to feed needed sustenance, and they turned to the best resource available, the bevy of North American big game animals that roamed the eastern part of the country.

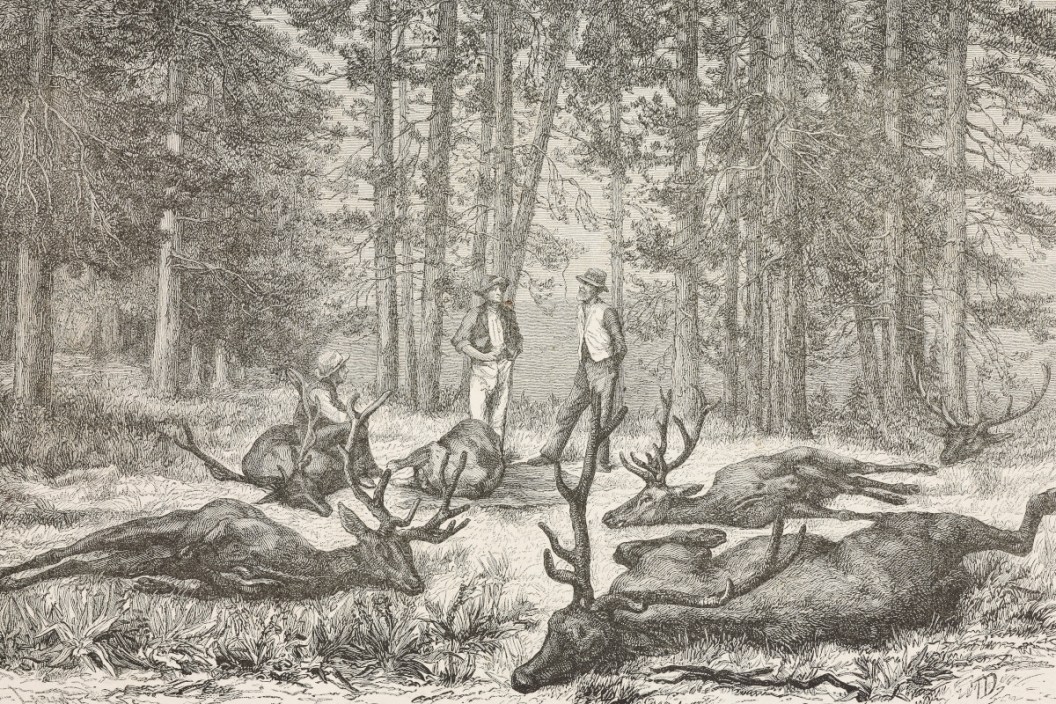

In the eastern-most states of the country, the cervus canadensis canadensis subspecies was quickly wiped out. With no game laws to stop them, people hunted with reckless abandon, something that would make most conservationists today cringe. The eastern elk vanished from South Carolina first in 1737, before the American Revolution even started. Other states soon followed as hunters gunned the animals down faster than they could reproduce. It probably also didn't help that the settlers were tearing up elk habitat to build homes, schools, churches, and fields for their crops. A few populations of elk held out in states like North Carolina, Vermont, and New Jersey until the late 1700s and early 1800s. However, by the mid-1800s, elk had been hunted completely to extinction in places like Arkansas, Pennsylvania, West Virginia, Ohio, Louisiana, and New York. Additionally, elk ranges in Canada were slowly wiped out around the same time. Some of the last holdouts for the eastern elk were Wisconsin, Michigan, Minnesota, and Missouri. Unfortunately, the last elk were shot in these states only a few years prior to 1900. Great elk herds that once roamed everywhere east of the Mississippi River were now gone forever.

Elk Are Reintroduced to the Eastern United States

Getty Images: paulsta

Many hunters will note that states like Kentucky, Tennessee, and Michigan all have small elk herds today. These animals are not ancestors of the ones previously hunted to extinction. Rather, they are the efforts of elk restoration efforts. Most of the animals found in the United States today can trace their lineage back to herds in places like Wyoming. Pennsylvania was one of the first states to start elk reintroduction efforts. The Pennsylvania Game Commission was created in 1895, and in less than 20 years, they were already looking into the feasibility of bringing their once great herds back. It's a good thing they did too, because it laid a foundation many other states followed.

Fortunately for the Keystone State, there was an excess of elk in Yellowstone and Grand Teton National Parks that the government was more than willing to relocate before the herd there started suffering starvation problems. According to the PGC, the first 50 elk were shipped back to Pennsylvania in 1913 via train. Two years later, in 1915, they released 95 more across six counties. Pennsylvania held its first elk season in 1923. Seasons would continue until 1931 when the population seemed to crash again. Much like conservation efforts with the wild turkey, wildlife officials and biologists struggled with reintroducing elk. Their numbers fluctuated wildly throughout World War II and through the 1950s and 60s. It wasn't until the PGC started working more on habitat improvement in the late 70s and 80s that the numbers started to increase.

Fast-forward to 1990 when the Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation stepped in to help the commonwealth acquire 1,600 acres of wooded and mountainous land known today as State Game Lands 311. The RMEF also contributed a ton of money towards elk deterrents for areas where farmers were experiencing heavy elk damage. The PGC also worked on massive relocation efforts to take the elk from problem areas where there was conflict with farmers to the few counties they are found in today. In 2001, Pennsylvania finally had another elk hunting lottery, and it has continued every year since then. The population of elk in Pennsylvania remains robust at around 1,000 animals.

Many other states have modeled their success after the trials and tribulations of Pennsylvania, especially the reintroduction model. Although these days, most eastern states choose to import their transplanted elk a little closer to home. North Carolina's were imported from Great Smoky Mountain National Park in 2002. Virginia imported their transplanted herd from Kentucky between 2012 and 2014. Just five years later, they were already talking about developing elk hunting opportunities, which is a testament to how far the science has come in helping these animals thrive. Some Canadian provinces like Ontario have also done their own reintroduction efforts in the last ten years.

Elk Management in Eastern States Today

Getty Images: Harry Collins

While we know that hunters would love for these newly introduced wildlife resources to spread far and wide to every corner of their historic range again, that's not likely to happen. In fact, if you start studying each state's management practices carefully, you'll see they are all quite aggressive in making sure elk don't expand too much out of their reintroduction sites. Again, this ties back to Pennsylvania and those farmers who were experiencing frequent elk damage. Many elk were outright poached by farmers in the decades after they were first introduced because the farmers were mad they were eating their crops. It kind of defeats the whole purpose of the work when citizens undermine restoration efforts like that. Then there's the fact that the eastern United States is much more densely populated than it was back in the early 1700s and 1800s. We have more roads, homes, businesses, and more that severely reduce the amount of habitat available for one of America's largest ungulates. It doesn't take much imagination to realize how much more dangerous unchecked populations of elk would be on the roads in the Midwest. We've already got enough of a problem with whitetail deer ending up as frequent road kills.

Sadly, all these factors mean most states must set aside specific areas for their reintroduced elk herds, usually on public land in low population areas. And many encourage hunters to shoot all elk that wander outside those borders. It's not because they want them all dead. There simply isn't a lot of places for them to live without becoming a huge nuisance to modern society. Just think about the vast, open places elk frequent in Wyoming, Colorado, Utah, New Mexico, and Arizona. The animals have room to roam there. Room that just isn't present the more populated areas of Pennsylvania, Michigan, or any of the other eastern states that used to hold these magnificent animals.

As great as conservation is, there are some problems that simply cannot be fixed through management practices and reintroductions. The greater lesson here may be the importance of habitat in conserving a species. Once we over-developed the eastern United States, it may have sealed the eastern elk's fate. The best thing we can do is learn how we failed the eastern elk, and then take the proper steps to make up for it however we can. Only by learning can we be better prepared for preserving these animals for future generations to enjoy.

For more outdoor content from Travis Smola, be sure to follow him on Twitter and Instagram For original videos, check out his Geocaching and Outdoors with Travis YouTube channels.