Fly fishing's traditional forward cast is a lovely, iconic image: the metronome of the angler's rod, suspending lengths of line above the water as if by magic. It's what we think of when we imagine casting a fly. But the more you fly fish, the more you will find yourself in situations when making a back cast isn't possible. This is where alternative casting strokes, like the roll cast, must be used.

Unlike the typical overhead cast, which uses the weight of the line in an aerial back cast to help load the rod, the roll cast instead relies on surface tension formed by the line making contact with the water. A forward roll casting stroke creates a loop, which then rolls the line forward. Because there is no aerial back cast, the roll cast is ideal for tight situations and keeping your flies in the water.

A roll cast can be used to deliver any type of fly but is especially useful when nymphing as false-casting weighted flies and an indicator is likely to result in a tangle. It's a simple cast, too, and can be learned by beginner fly anglers with just a little practice. Once you get the hang of roll casting, you'll begin seeing how efficient, and effective, it can be.

Tools for Roll Casting

Getty Images | You can roll cast nearly any fly to nearly any fish.

While some line types are better for making roll casts than others, just about any fly line will perform if the mechanics of the roll cast are correct. Likewise, rod type or length, and reel, are secondary to the technique. The bottom line is that any fly rod and reel combo, paired with a fly line of complimentary weight (Read: a 5-weight line with a 5-weight rod, etc.) will be able to make a roll cast. But getting the technique right is key.

That said, if you're new to roll casting or just want to practice, use a tapered leader with a few short pieces of yarn tied to the end. Once you're comfortable, try roll-casting a single unweighted fly on the water. From there, introduce progressively heavier rigs with weighted nymphs, streamers and indicators—basically any fly in your fly box can be roll cast. The mechanics will remain the same, but dynamics will change as you add weight and objects with increased wind resistance.

How to Roll Cast

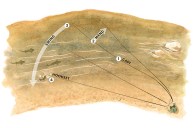

1. Prepare: Make a D-loop.

A D-loop is the shape of your line when you're in the correct starting position. To get there, bend your casting arm at the elbow until the tip of your rod is just behind the plane of your body. The reel should be about even with your ear, and the rod should be canted away from your casting shoulder ever so slightly.

Lifting the rod should be slow and steady, such that it drags the line across the surface of the water. Ideally, this will straighten the line in front of you. If the line is in a pile at your feet, there won't be enough line tension to load the rod and make the cast.

Once you've brought your rod to the starting position for the cast, it's important to make a slight pause. This will anchor the line to the surface of the water and greatly aid in the forward casting stroke.

2. Make the Roll Cast.

There's an adage that says if you can hammer a nail, you can make a roll cast. That's true enough, but it suggests that a roll cast requires the same slamming motion you make when hammering. Doing so won't work.

Instead, I find the image of swatting a fly to be much more appropriate. Imagine a wall about a foot in front of you. With your rod/swatter, your motion starts slow and accelerates to a stop, your wrist flicking at the end such that the flat head of the fly swatter makes contact with the wall without smashing your knuckles.

A successful roll cast uses the same mechanics. A smooth acceleration of the fly rod from the starting position to "the wall" applies energy. As the fly line cuts through the water, there is friction, which bends, or loads, the rod. The crisp stop transfers the energy from your casting stroke through the rod and into the fly line. A final small rotation of the wrist focuses all that energy toward your target. Splat goes the fly, all the way across the river.

If your cast is falling flat or landing in a jumble in front of you, you're either overpowering the forward cast or dropping your rod too low. Keep at it and pay attention to how your line and fly respond to your adjusted technique.

3. Don't Cross the Tracks.

Roll casting is best executed when your forward casting stroke runs parallel to the line that's stretched out in front of you on the water like train tracks. If you try and cross the tracks—for instance, attempting to roll cast out of swinging a wet fly downstream—your line will double over itself and your fly will inevitably catch, causing a tangle.

A perfectly performed roll cast will send a round loop unfurling alongside the line lying on the water. Be cautious not to lay your roll cast outside the line that's on the water, for as the line rolls forward, the end of your line—with a sharp hook point immediately behind—will zip toward you before being deployed by the cast. Roll casting to the inside of the anchored line will keep the fly away from your body, and more importantly, face.

When to Use the Roll Cast

Getty Images, Kick8989 | Roll casting is extremely useful when you're fishing tight, brushy spots.

Because the roll cast doesn't rely on an aerial back cast to load the rod, it's an excellent option for tight quarters. But it's also a technique that can be used elsewhere. Imagine a trout has just taken your fly but you've missed the hookset. Your fly line is lying limp on the surface of the water. A roll cast can quickly redeploy the fly without the need for false casting. Or perhaps you need to get some line off the guides to start a forward cast; use a quick roll cast.

The roll cast is also a key building block of more advanced casting methods. Mastering its mechanics will open the door to single- or double-handed spey casting.

The more comfortable with it you become, the more applications for this simple — and exceedingly useful — casting technique you will discover.