The name Carl Akeley is likely to be unfamiliar to most of us, despite some of the lasting impacts he has made on science and conservation.

Akeley not only made his mark as a successful inventor, biologist, conservationist, author, hunter, sculptor, and nature photographer, but he was also the man responsible for elevating taxidermy to a previously unknown level of realism. He turned a profession into an artform.

A nature lover with diverse interests, Akeley found himself with the circle of friends of the legend himself, Theodore Roosevelt. Akeley was responsible for establishing several nature preserves and national parks, including the first wildlife sanctuary in Africa. He influenced the Hollywood film industry with a motion picture camera he invented. He was also one of the first humans to study mountain gorillas and the first to film them in the wild. He was a master of all his chosen trades, dedicated to science and preservation, and an adventure seeker.

Along the wild ride of his life, he was stomped into the ground by a raging elephant, used a crocodile carcass as a raft to cross a deadly river, and was charged by three enraged rhinoceros at the same time. Oh, and he killed a revenge-seeking 80-pound leopard with his bare hands.

All in a day's work, right?

A young Carl Akeley Field Museum

"Badass" only hints at the character of Carl Akeley. The man was as close to Superman as a mortal can get. Author Hawthorne Daniel described Akeley as "one of the most remarkable Americans of his time. No man that I know of can equal his amazing versatility."

In the Beginning

Carl Ethan Akeley was born May 19, 1864 in Clarendon, New York. He was a skinny farm boy who took a borderline obsessive interest in nature and wildlife at an early age. He saw an exhibit in Rochester that sealed his fate: the display contained several dozen stuffed critters by taxidermist David Bruce. He was enamored.

At 18 Akeley apprenticed with Bruce in Brockport, but Bruce quickly recognized his mentee's talent and recommended that Akeley return to Rochester to study under the preeminent taxidermist of his day, Henry Ward, at Ward's Natural Science Establishment.

Ward took the young Akeley on for a measly $3.50 a week, which was nothing even back then, with the stipulation that Akeley work from 7:00 am to 6:00 pm. Oh, and no sick leave or holidays.

Akeley found the work disappointing and unsatisfying, and he received no formal training working under Ward. He was basically nothing more than a manual laborer for Ward, who didn't care about the kind of realism or artistic expression that interested Akeley. Akeley complained that "the profession which I had chosen as the most satisfying and stimulating to a man's soul was neither scientific nor artistic as it was practiced at Ward's."

Taxidermy pre-Carl Akeley

Trip Advisor

Akeley's version of taxidermy

AMNH

Back in those days taxidermy provided the source material for all of those comical 'Bad Taxidermy' photos we see online today. The mounted specimens they produced can generously be described as horrendous, or a thing of nightmares. They bore little resemblance to actual living animals.

Basically, taxidermists stuffed animal skins full of straw or cotton - the 'upholsterer's method' - and roughly formed the body to more closely resemble a pre-adolescent child's drawing of an animal. Your average stuffed animals exhibited buggy eyes, obvious seams and stitching, and awkwardly positioned legs. They were abysmal curiosities and had practically zero educational impact on their audience.

Jumbo the Elephant

Ward ultimately fired Akeley for falling asleep on the job. It's little wonder Akeley was tired; his contract stated that he could only work on his own advanced taxidermy skills at night. But Ward later realized that he wouldn't find an employee who worked as hard as Akeley - for as little money - and hired him back. It was during his second round with Ward that Akeley got his big break.

Ward assigned the task of mounting Jumbo, P.T. Barnum's famous elephant, to Akeley and William Critchley. Critchley was a caring and competent taxidermist who took Akeley under his wing. A train accident had killed the prize elephant, and the project took five months to complete. It earned Akeley a certain measure of notoriety.

Akeley also made friends with another fellow taxidermist while at Ward's, one William Morton Wheeler. Wheeler advised Akeley to apply at the Milwaukee Public Museum.

Akeley did just that, and for six years he refined his revolutionary taxidermy method. Milwaukee was where Akeley also developed his idea to show his lifelike animals in their natural settings, a natural complement. He gave his dioramas as much attention and effort as he did the actual creatures he was mounting.

"Muskrat Group" - one of Akeley's early dioramas for the Milwaukee Public Museum Wikipedia

After leaving Milwaukee, Akeley did a few years as an independent contractor (doing work for, among others, the Smithsonian Institution). Then, in 1896, he joined the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago. It was then that his career really took off, and his taxidermy methods truly became astounding.

A Revolutionary Method of Displaying Wildlife

Where others before him had done questionable work literally 'stuffing' animals, Akeley decided that his creatures must educate and inspire the public in ways they had never seen before. He dedicated himself fully. He studied the anatomy and biology of his creations, to the point that he became a legitimate scientist of wildlife biology.

Akeley developed a complicated method of crafting forms around which the animal's skin would be attached. He used clay, wire, and wood, and sometimes even the animal's own skeleton to create forms from which he then molded papier-mâché mannequins. The mannequins showed the animal's musculature and veins, and were posed in extremely natural, lifelike postures.

The forms we see taxidermists use today are a direct result of Akeley's creative genius. Additionally, Akeley developed a method of skinning that hid the seams when the hide was sewn back together over the form, always going the distance to bring life back into the animals that had lost theirs.

Carl Akeley modeling an elephant for Hall of African Mammals in 1914. AMNH

As mentioned, he put tremendous care into the displays he built just as he did in his working restoring his subjects. Akeley brought realism to the animals he worked on, so it only made sense that he would bring their environments to life as well. He developed methods to reproduce natural-looking flora, such as grass and leaves, and did so using beeswax, wire, thread, and other materials. He labored tediously to create the natural settings specific to each species where they would be mounted.

Akeley eventually left The Field Museum and began working as the chief taxidermist for the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) in New York City in 1909.

The AMNH financed Akeley's expeditions to Africa, where he hunted for specimens to fill his dream of a hall of taxidermied African wildlife. He felt that African game was quickly going the way of the dinosaur. Fearing extinction, he wanted to build something that would allow future generations to be able to see those beasts in their natural habitats, before they were all gone.

Akeley began work on his massive project, collecting the animals himself during his African expeditions. Unfortunately, he died before getting the opportunity to finish the project. After his death, his work was continued by others. The AMNH christened it the Akeley Hall of African Mammals. It is a monumental achievement and a legacy to the man rightly called the Father of Modern Taxidermy.

The Akeley Hall of African Mammals AMNH

At the center of the African hall is a freestanding diorama of eight cow, yearling, and bull elephants, surrounded by 28 habitat dioramas displaying the diverse landscape and wildlife of the continent. Included are ostriches, rhinoceros, giraffes, a pride of lions, warthogs, mountain gorillas, and more, all in their natural habitats. The animals are posed to exhibit behaviors observed in the wild.

Audiences flocked to see Akeley's dioramas and lifelike mounts. It is just as awe-inspiring today as it was when it was fresh and new - a timeless contribution to science.

Akeley's Camera and Cement Gun

While he was busy setting the taxidermy world aflame with productive change, Akeley also finished quite a few other unique projects. He authored articles for National Geographic and wrote several books, including a children's book. He also authored In Brightest Africa, which told of his hunting experiences and getting up close and personal with gorillas.

He also achieved critical artistic acclaim as a sculptor. Several of his pieces are on display in museums today.

With an imaginative mind like Akeley had, it seems only natural that he would also be an inventor. He received more than 30 patents for his inventions, which included the unique and highly adaptable Akeley Motion Picture Camera.

The camera was, like other things Akeley put his hands to, transformative. It had the ability to smoothly pan and tilt, and capture fast action sequences fluidly and seamlessly.

Akeley's "pancake camera"

Field Museum

Akeley used his "pancake camera" (so-called because of its shape) to film the first-ever motion pictures of gorillas in the wild, in what is now the Democratic Republic of Congo.

The camera became a favorite of explorers around the world and was employed on countless famous and noteworthy expeditions. It also became the favored camera for World War I correspondents who preferred its light weight and mobility for producing newsreels of the war.

Hollywood also exploited the advantages of the camera, using it in several famed motion pictures, including Nanook of the North (1922), Simba (1928), Frank Capra's Flight (1929), Howard Hughes' Hell's Angels (1930), the chariot races in the 1926 film Ben Hur, and William Wellman's Wings (1927), which won the Academy Award for Best Picture.

It became such an indispensable piece of equipment that scripts actually called for "Akeley shots," signifying that Akeley's camera was the one for the job.

In addition to the camera, Akeley also invented a search light used in WWI and, notably, a tool that sprayed a concrete mixture like a firehose. His "Shotcrete" invention was (and still is) a viable tool to repair and build walls, pools, and other structures. President Teddy Roosevelt actually adapted it for use in building the Panama Canal.

Almost Getting Killed . . . the First Time

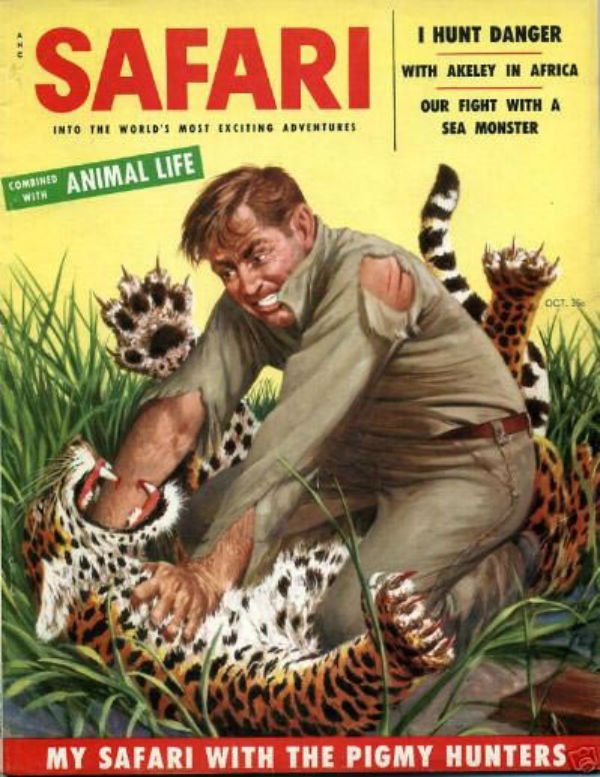

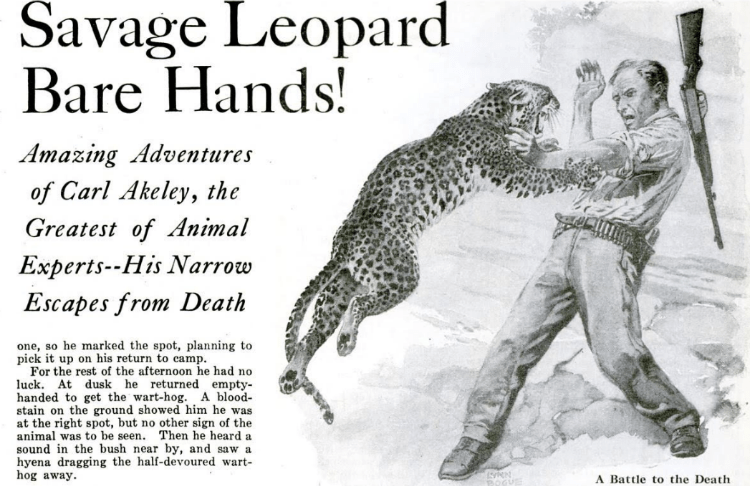

It was Africa that truly thrilled Akeley's soul. He made his first expedition in 1896, and it was during this trip that Akeley had an encounter that would make him the subject of adventure magazines and pulp fiction.

Popular Science article, Dec. 1925 Google Books

Akeley was out in the Somaliland bush one day, hunting for specimens to bring back to America for mounting. He had little success, but he did shoot a nice warthog. He left the hog where it lay and continued hunting, intending to retrieve it on his way back to camp.

Upon his return to the spot where he shot the warthog, he saw only a spot of blood and drag marks in the dirt where the warthog's carcass should be. Suddenly, he noticed a shadowy blur in the nearby brush. He lifted his rifle and fired. A pain-maddened snarl greeted Akeley.

Accounts of what happened next vary, but ultimately Akeley fired several more times, missing multiple times and finding his mark at least once. But that one time only served to enrage a maddened 80-pound leopard that leaped for Akeley's throat.

Akeley instinctively lifted his right arm to defend himself, and the bloodthirsty cat bit down hard. The scene was a whirlwind of teeth, claws, and desperate human limbs trying to fend off the feline cyclone.

If you've ever tried to hold a house cat that didn't want to be held, you might get a weak idea of what Akeley was going through. He was caught in a life and death struggle with 80 pounds of leopard intent on killing him.

"I felt no pain," Akeley recounted, "but I certainly never thought for a moment that I was going to come out alive. I was rather calm, as a matter of fact, except for a tremendous and wildly pleasant thrill I felt, knowing that I was battling for my life. I remember very clearly thinking of a conversation I once had with a friend when, at the World's Fair at Chicago, we had seen a statue of an Indian fighting a bear, very much as I was fighting this leopard. We wondered if the man felt any pain. 'Well,' I thought, 'I could tell him now. But I won't have a chance'."

While his right arm was being mauled by the leopard, Akeley grabbed the big cat by the throat with his left hand. He desperately tried to strangle the beast and keep the slashing claws from ripping open his belly.

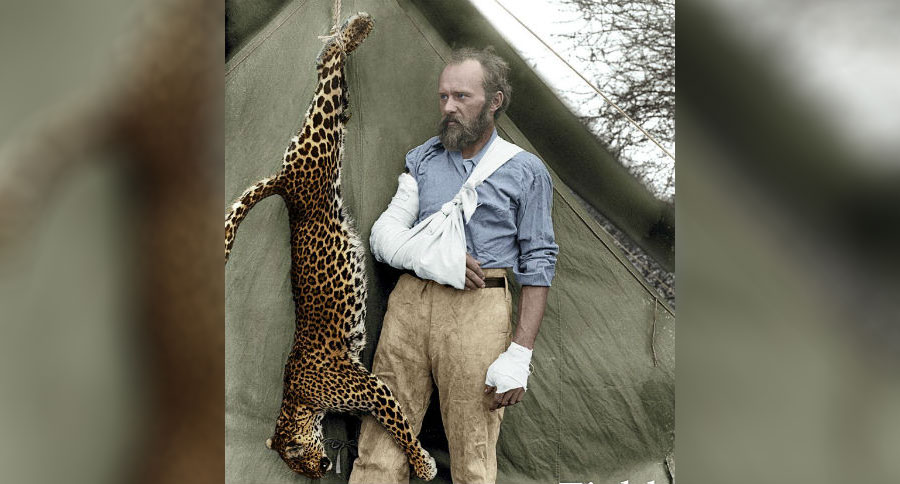

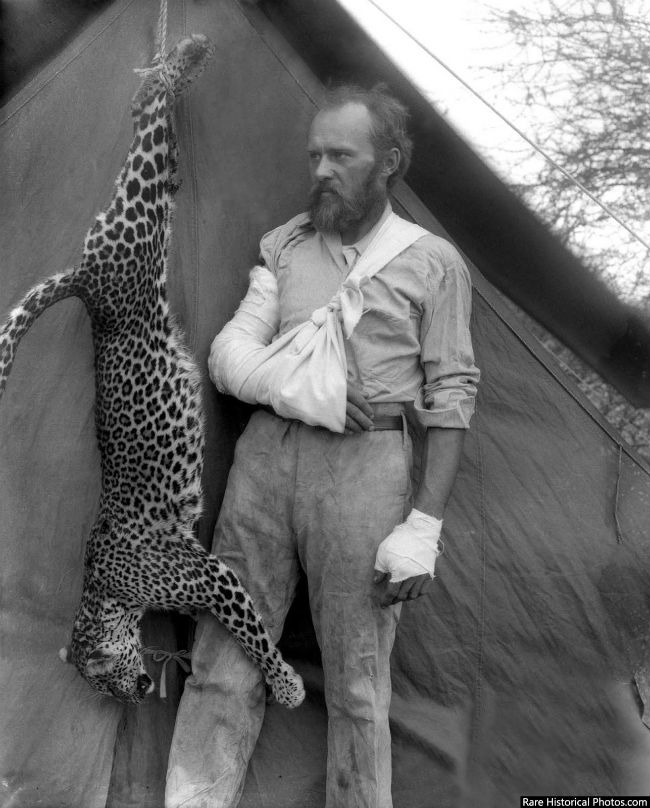

Carl Akeley with the leopard that nearly killed him, 1896. Rare Historical Photos

This was life or death, and things did not look good for Akeley. There are very few instances where humans have overtaken a beast like a leopard with their bare hands.

But Akeley had the advantage of his free left hand. Plus, this cat didn't know it was trying to devour Carl Ethan Akeley, a man with more grit and determination than your average titan.

"With my left hand at the animal's throat I pushed him down my right arm, for he was chewing all the time," he said. "I dragged my whole arm through his jaws, and finally I got my right fist in his mouth." Akeley shoved his bloody right hand and arm as far down into the spotted buzzsaw's gullet as he could.

"We were both getting weak, and at last we went down," Akeley continue. "Luckily the leopard was underneath, and as we fell my knees struck his chest, and I heard a rib snap."

That was all Akeley needed. "So I jumped up and down on his chest with my knees, while I still had his throat with my left hand, and held my right hand in his mouth. I caved his ribs in, and finally he gave a gasp and released his hold."

Whether through skill, luck, or a combination of the two, Akeley finished the beast off with a knife and made it back to camp. His men pumped his shredded arm full of antiseptics to stave off infection from the cat's many bite marks. They brought the leopard into camp where it was discovered that Akeley had hit it twice with superficial bullet wounds.

Adventurers around the world thrilled at the photo of a bandaged Akeley standing next to the hanging leopard. Depictions of the attack, some taking more artistic license than Akeley would likely approve of, accompanied magazine articles with overly dramatic headlines.

The photograph is deceiving, as the leopard looks smaller than its 80 pounds. But the grim look on Akeley's face was surely enough to give any of the leopard's feline relatives second thoughts about revenge; he's even tougher than he looks.

Almost Getting Killed . . . the Second Time

The second time Akeley stared death in the face was even more severe than his encounter with the leopard. It happened in 1911, while hunting elephants in the forests of Mount Kenya.

Following a large track with his gun bearer, Akeley heard a rustling behind him and turned. Suddenly a massive, enraged elephant burst through the foliage and bore down on him.

Before he could lift his rifle the beast slammed into Akeley like a battering ram, slicing him across the face with its sandpaper-like trunk. Akeley quickly came to his feet and wiped the blood from his eyes, only to see the maniacal pachyderm bearing down on him with a deadly six-foot long ivory tusk.

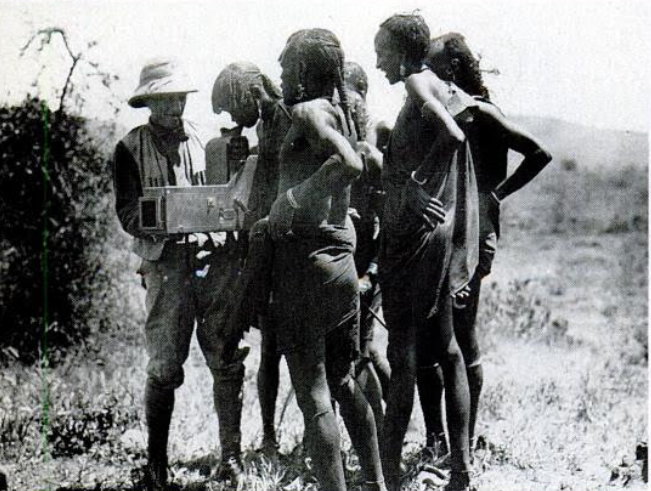

Akeley showing his camera to a group of Turkani natives.

Google Books

Immediately deciding that he'd rather not be a bloody ornament at the end of an elephant tusk, Akeley grabbed the tusk and swung himself in between the two long ivories. The maddened mammoth then used his tonnage to headbutt and drive Akeley straight into the earth, attempting to flatten him like a pancake.

"...I saw a great tusk aimed directly at my chest," Akeley retold the tale. "I grabbed it with my left hand, and grabbed the other tusk with my right, and swinging in between them, I went down on my back."

The force of the blow shattered Akeley's rib cage, and his body looked like a rag doll abused by the Incredible Hulk. Before he lost consciousness, Akeley recalled the elephant's shark-like eye staring back at him with apparent glee that he had pulverized this puny human.

"So there I was between the great tusks," he said, "which he plunged into the ground on both sides of me, with his curled-up trunk against my chest. I have a clear recollection of that instant. I had the sensation of being crushed, and I remember looking up into what seemed to me a very small and wicked eye, just a little above me, and I knew I could expect no mercy from it. And then he gave a sort of wheezy grunt as he plunged down, and that is all I recall."

Akeley following his elephant attack Google Books

The natives believed Akeley was dead. They left him lying in an elephant head-shaped depression for several hours as it rained and turned the shallow pit into a mudhole. Akeley eventually moved, and the surprised natives got him back to camp and then to civilization, where he spent six months convalescing.

Apparently the elephant's tusks had hit a rock while trying to drive Akeley through the earth, which stopped his pile driving effort and probably saved Akeley's life.

More Near-Death Incidents

Elephants and rhinos charged Akeley at least 20 times during his career. One time he was charged by three rhinos from three different directions at the same time. When recounting this incident, he replied simply that rhinos had bad eyesight and were usually more interested in charging than in killing.

Another time a herd of elephants stampeded through his camp, the resulting earthquake causing a scene of pure chaos and some fine gymnastics by Akeley as he rolled out of the way of rumbling pachyderms and falling trees.

Theodore Roosevelt accompanied Akeley on an expedition in 1909. Akeley dedicated his book In Brightest Africa to Roosevelt.

Akeley and his wife Mary, on his final safari, 1926. Google Books

Through Akeley's career he made five expeditions to the continent. His last was in 1926, where he traveled to the Belgian Congo with his second wife, Mary Jobe Akeley, a noted adventurer in her own right and 20 years Akeley's junior.

It was on this trip that Akeley contracted malaria and dysentery, and ultimately succumbed. He was 62 years old, but had the stamina and carriage of a man in his twenties.

Akeley's expressed his interest in hunting and collecting animal specimens was for purely scientific reasons. He felt it was his duty to try to preserve these creatures for future generations to appreciate, in dioramas showing their natural habitats and behaviors, before they were all gone.

Towards the end of his career, his viewpoint shifted and he started to question the morality of killing the animals he mounted. He started to feel like a murderer. It was after this perspective change that he threw himself into preservation and conservation work, and like with everything else he did, made lasting impressions in that field.

He advocated for the preservation and protection of many species by convincing world leaders like Roosevelt to establish national parks and wildlife preserves. Akeley persuaded King Albert of Belgium to establish what is now called Virunga National Park. It is a place where his beloved mountain gorillas are protected. Virunga is also Africa's first national park.

Akeley lies where he fell in east Africa, between the volcanos Mikeno and Karisimbi. It took two-dozen porters three days, working in 12-hour shifts, to carve his gravesite in the hard volcanic rock. He lies only a couple miles from where he encountered his first gorilla in 1921.

It was Akeley's last wish. "I want to die in the harness," he told his wife. "I want to be buried in Africa."

Like what you see here? Experience more articles and photographs about the great outdoors at the Facebook page, Stumpjack Outdoors.

READ MORE: Historic Outdoor People: John Muir, 'Father of the National Parks'