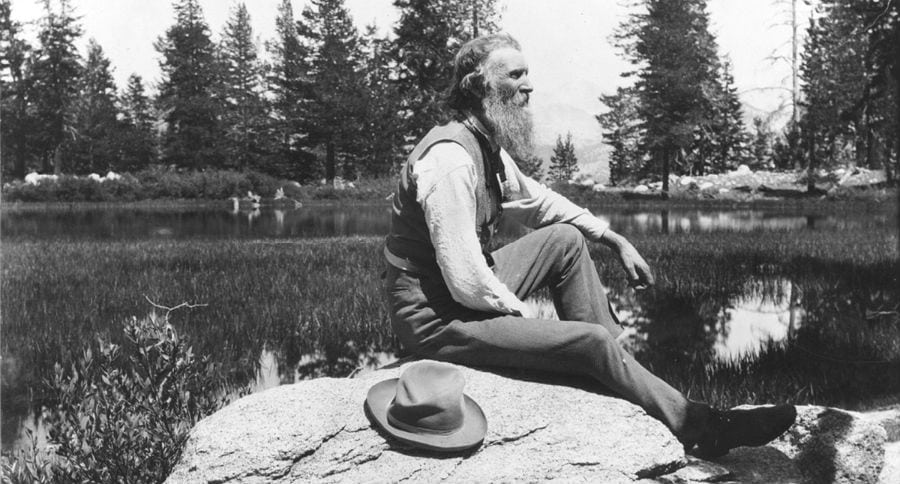

John Muir is one of the patron saints of the American wilderness. His writings helped shape the modern conservation movement and our understanding of the natural world.

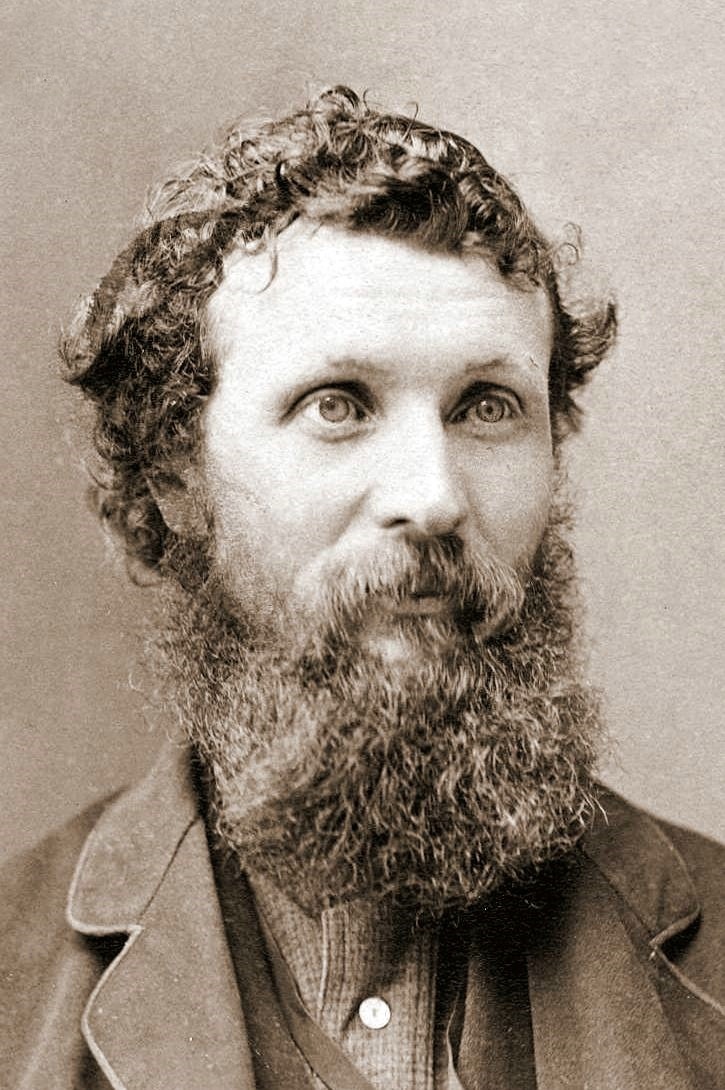

If ever the old saw about following your passion was apropos for a man, it was certainly apt advice for John Muir. Muir led a largely unremarkable life as a 19th century vagabond flower child of sorts, until he begin to put his thoughts into writing. It was with the written word that he changed the way many Americans viewed the natural world.

With the encouragement of friend and mentor Jeanne Carr, Muir wrote about the wilderness with elegance and zeal. His writings were rife with spiritual overtones and captured the imagination of millions of readers, readers who were ready to embrace his vision of the wilderness as a near-religious experience.

Muir's biography is well-documented and makes for an interesting read. But it is his later life's work that laid the groundwork for the enduring legacy Muir left. Born in 1838 in Scotland, Muir's family emigrated to America in 1849. Always keenly interested in nature, it wasn't until Muir was in his 40s that his life's passion was embraced on a national level.

Muir the writer

Writing for outdoor magazines Muir was able to successfully communicate his love for the high country of the American West. The Sierra Nevada, Yosemite and other pristine wilderness areas provided inspiration and subject matter. Writing for periodicals such as Overland Monthly, Scribner's, Harper's Magazine and The Century made him famous.

He wrote with the passion of a Sunday preacher, an apt description given Muir's belief that the wilderness was a conduit to communicating with God. Much of America agreed with Muir, or at least yearned to experience the wild as he described it.

In spreading the gospel of nature as divine, Muir became the leading authority on land that was wild and unspoiled. He wrote 300 articles and 12 major books recounting his wilderness travels and experiences.

When other naturalists and politicians came calling, Muir was only too happy to share the good news with them.

Muir's activism

That other giant of the naturalist movement, Ralph Waldo Emerson, visited Muir at his cabin in Yosemite. Muir was also friendly with noted Yosemite photographer Carleton Watkins, scientists Joseph LeConte and Henry Fairfield Osborn, U.S. Forest Service Chief and naturalist Gifford Pinchot, railroad executive E.H. Harriman, and many other luminaries of the day.

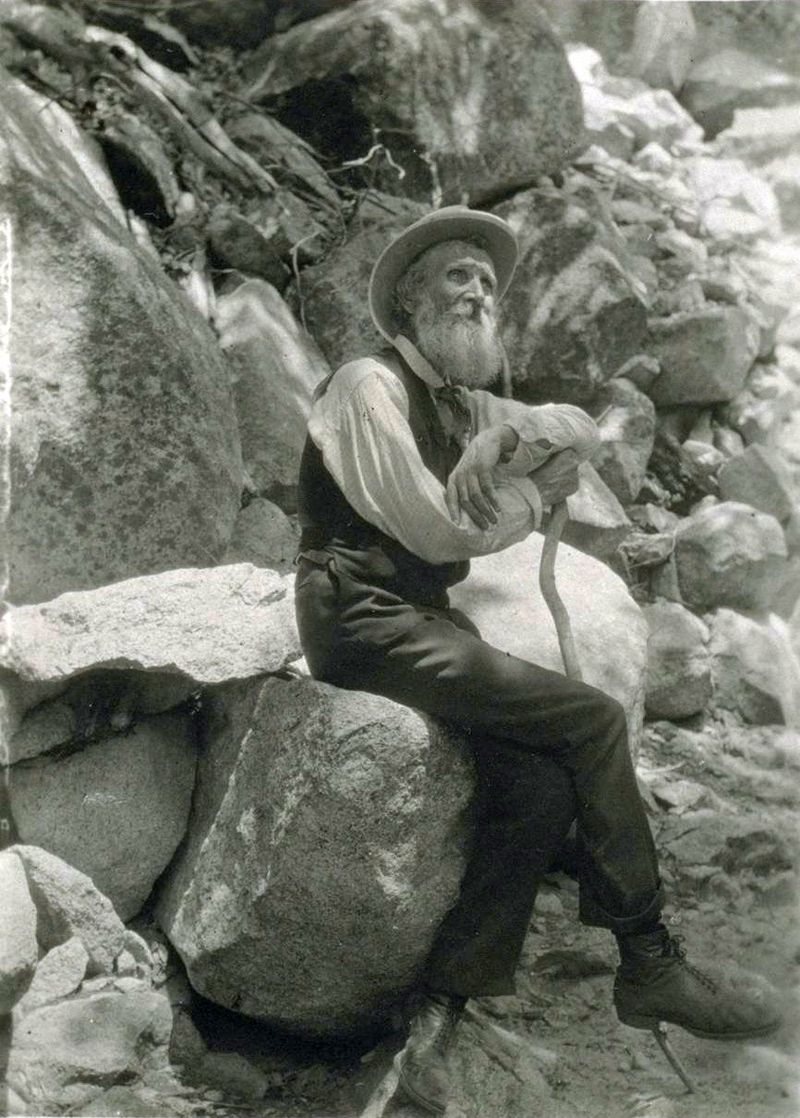

As he approached later life, Muir made a conscious decision to go from living in the wild and writing about it to actively advocating for its preservation. Bonnie Gisel, curator of the Sierra Club's LeConte Memorial Lodge and the author of several books on Muir, declared, "The question was now how to protect it. By leaving, he was accepting his new responsibility. He had been a guide for individuals. Now he would be a guide for humanity."

In 1889 The Century magazine editor, Robert Underwood Johnson, camped with Muir in the Yosemite. Johnson agreed to publish any articles Muir wrote on the negative impact of livestock on high mountain meadows.

Platforming on two articles that Muir wrote for The Century, the two men campaigned the U.S. Congress to turn Yosemite into a national park. The following year, 1890, Congress did just that, passing a bill officially creating Yosemite National Park.

Buoyed with the Yosemite success, Muir also had a hand in securing Sequoia, Mount Rainier, Petrified Forest and Grand Canyon national parks. As a result, Muir has justifiably been called the "Father of Our National Park System."

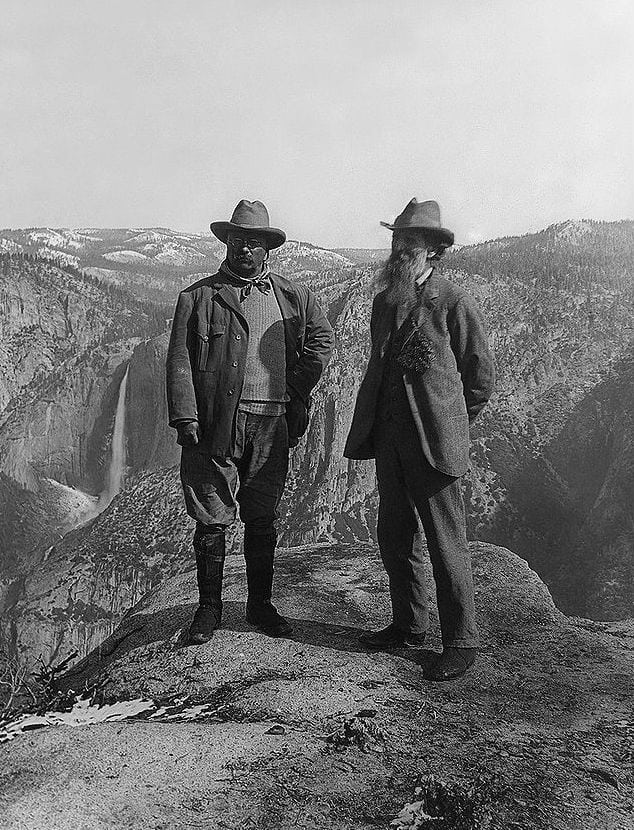

President Roosevelt

One famous story illustrates the influence that Muir wielded. In 1901 he published Our National Parks, which garnered the attention of President Theodore Roosevelt. In 1903 Roosevelt accompanied Muir to Yosemite. During the trip the President and Muir were able to lose their Secret Service detachment and slip away for three days of wilderness camping.

They camped at Glacier Point where the pair talked of conservation and America's natural resources. Muir revealed how the state was mismanaging and exploiting the valley's resources. Their time together made a lasting impact on both men.

Roosevelt later said, "Lying out at night under those giant Sequoias was like lying in a temple built by no hand of man, a temple grander than any human architect could by any possibility build." It was this experience with Muir that compelled Roosevelt to return federal protection and management of Yosemite Valley and the Mariposa Grove as part of Yosemite National Park.

Muir's Legacy

In 1892 Muir co-founded the Sierra Club, one of the world's first large-scale environmental preservation organizations. The club set lofty goals from the start. It immediately helped establish Glacier and Mount Rainier national parks. The club secured the preservation of California's coastal redwoods, and convinced the California legislature to let the federal government manage Yosemite Valley.

While the Sierra Club's stance on hunting is rather weak, the impact the club has had on environmental issues cannot be understated. The club continued to grow in influence and membership after Muir's death, and has helped establish a number of additional National Parks.

Muir's philosophy of a nature as a conduit to the divine reshaped the way Americans viewed the natural world. His philosophy is still as viable and relevant today as it ever was. Muir's work in helping to establish the country's National Parks makes him one of America's most influential figures. His writings and activism helped shape America.

If the places that are named after someone are any indication of a person's far-reaching influence then Muir's impact is certainly monumental. The John Muir Trail, the Muir Woods National Monument and Mount Muir were all named in his honor. Other places include Muir Beach, Muir Grove, Muir Glacier, Camp Muir, John Muir College, Muir Inlet, Muir Point, a number of schools, highways and even medical institutions.

Enos Mills, a contemporary of Muir's who established Rocky Mountain National Park, opined that Muir's writings made him the most influential force of the century. John Muir's ability to describe and exalt nature continues to inspire millions of people.

Like what you see here? Experience more articles and photographs about the great outdoors at the facebook page, Stumpjack Outdoors.

NEXT: Bask in the Beauty of the Grand Teton Mountains on Film

WATCH