An invasive tick species has been spotted across Ohio in various locations over the past few years—and researchers at Ohio State University fear it poses a significant threat to livestock, according to a recently published report.

The trouble with Asian longhorned ticks is that they reproduce rapidly and quickly establish firm populations within an area—and they're impervious to traditional pesticide methods.

The first documented discovery of an Asian longhorned tick in Ohio occurred in 2019, when Risa Pesapane, an assistant professor and tick researcher at Ohio State University, found one on a stray dog. The second was collected from a cow in Jackson County in June 2021. The third came later that year, when a farmer in the southeastern portion of the state called the university to report that three of his cattle—previously healthy—had died from blood loos after becoming infested by the ticks.

"One of those was a healthy male bull, about five years old," Pesapane said. "Enormous. To have been taken down by exsanguination by ticks, you can imagine that was tens of thousands of ticks on one animal."

Pesapane and her colleagues deployed to the farm to conduct research. They collected almost 10,000 ticks in less than two hours, leading them to estimate that more than 1 million of the tiny brown ticks likely inhabited the roughly 25-acre pasture.

Getty Images, Frizi

What sets these ticks apart from other varieties is their ability to reproduce asexually. Each female lays up to 2,000 eggs at a time, and all 2,000 of those female offspring is able to do the same. A full-grown cow serving as a blood host can quickly become overrun by thousands of ticks and drained of life.

"There are no other ticks in North America that do that," Pesapane said. "So they can just march on, with exponential growth, without any limitation of having to find a mate. Where the habitat is ideal—and anecdotally it seems that unmowed pastures are an ideal location—there's little stopping them from generating these huge numbers."

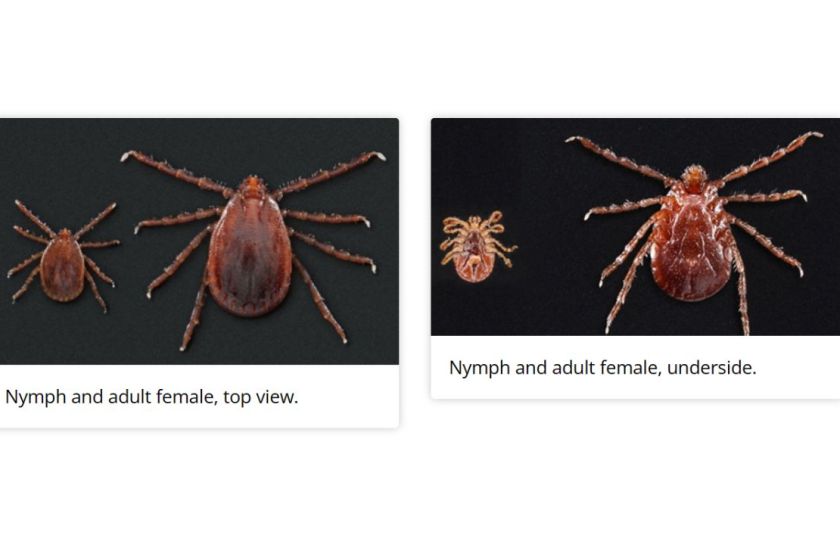

Not only that, but they are also so tiny—the size of a sesame seed during nymph stage on up to a pea size during adulthood—that they can easily hide in brush and grassy vegetation. That makes them difficult to kill with pesticides that need to come into contact with the insects. In fact, pesticides were applied at the farm where the cows had died; the next summer, the ticks were back and thriving.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

"It would be wisest to target them early in the season when adults become active, before they lay eggs, because then you would limit how many will hatch and reproduce in subsequent years," Pesapane said. "But for a variety of reasons, I tell people you cannot spray your way out of an Asian longhorned tick infestation—it will require an integrated approach."

The Asian longhorned tick first appeared in the U.S. in 2017 in New Jersey. As of 2023, they have been found in Arkansas, Connecticut, Delaware, Georgia, Indiana, Kentucky, Maryland, Massachusetts, Missouri, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Tennessee, Virginia, and West Virginia, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). And the Ohio farm wasn't the first to report cow death from tick infestation; five cows in North Carolina died from blood loss in 2019.

At this time, Asian longhorned ticks are not considered to be a threat to human health, but research is ongoing. It's known that this species prefers large livestock and wildlife, such as cattle and deer, as hosts. This differs from native tick species—such as the blacklegged tick, lone star tick, and American dog tick—which are known to seek out humans as much as animals.<< THIS FACT NEEDS A SUPPORTING BACKLINK

Of the ticks gathered at the Ohio farm, only a few tested positive for Anaplasma phagocytophilum, a harmful pathogen that can make people and animals sick. Still, all ticks still can serve as a vector to carry tick-borne illness, however, and should be avoided.