The Great Lakes' cold waters might not make for the most pleasant swimming, but it does have one thing going for it: excellent preservation capabilities. The frigid fresh water is renowned for the impressive collection of shipwrecks and downed planes that rest on the bottom of the Great Lakes, making it a utopia for underwater archaeologists and recreational scuba divers alike.

But now, an invasive species is negating the pristine preservation powers of the Great Lakes and destroying centuries' worth of history in the process.

Why the Great Lakes Are a Hot Bed for Shipwrecks

Velvetfish, Getty Images

Since the Industrial Revolution, the Great Lakes have been a thoroughfare for ships transporting valuable resources inland, and port cities such as Milwaukee, Detroit, Chicago, and Toledo have enjoyed a lively maritime trade due to these ships. However, the ever-changing weather of the region also made it a dangerous place, with an estimated 10,000 shipwrecks in the Great Lakes, half of which remain undiscovered. Added to this are numerous planes that went down in the region, including 200 military aircraft lost during World War II.

These wreckages provide important archaeological and historical information about our country—information that is quickly being destroyed by an unlikely culprit: the invasive quagga mussel.

A Hungry and Hardy Invasive Species

Quagga mussels, a freshwater species native to Ukraine like the similarly invasive zebra mussel, originally made their way to the U.S. through transoceanic ships' ballast water and spread throughout the states via recreational vessels.

Quagga mussels are particularly voracious and are hungrier, hardier, and more tolerant of cold water than zebra mussels, making them unfortunately well suited to the cold, deep waters of the Great Lakes. After 30 years of colonization, quaggas have displaced zebra mussels as the dominant mussel in the Great Lakes, according to the Center for Invasive Species Research at University of California Riverside. In 2000, zebras made up more than 98 percent of mussels in Lake Michigan but just five years later, quaggas represented 97.7 percent of mussels.

Though only growing to the size of a finger, quagga mussels are prolific breeders and, en masse, incredibly destructive in U.S. waters. Both quagga and zebra mussels can clog intake structures like pipes, and encrust docks, boats, and beaches. They also kill native freshwater mussels by attaching to their shells or by eating all of the available food.

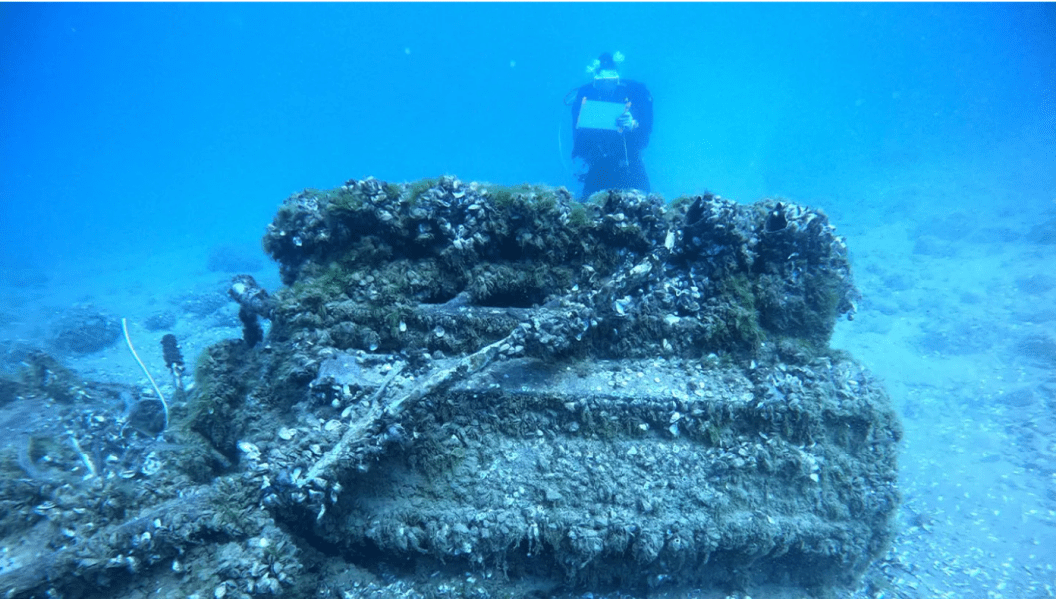

Now, quaggas also taking down centuries' worth of maritime history in the Great Lakes. Archaeologists told AP News that the mussels cover nearly every shipwreck and downed plane in the lakes, except for Lake Superior, where scientists believe less calcium in the water is preventing quaggas from making their shells.

Because the mussels are able to burrow into wood, they can build themselves into layers so thick that the weight of the mussels crush shipwreck walls and decks. They cannot be removed without stripping some of the wood away, damaging the ships further. Metal airplanes and ships aren't safe either; the mussels also produce an acid that corrodes steel and iron.

The Race to Save Great Lakes' History

imagixian, Getty Images

Michigan's state maritime archaeologist Wayne Lusardi is at the forefront of the movement to save as many shipwrecks and planes from the mussels as possible. He's pushing to raise more pieces of a World War II plane out of the water to save it from the quagga mussels. Flown by Frank H. Moody of the famed Tuskegee Airmen, it crashed in Lake Huron in 1944.

"Divers started discovering [planes] in the 1960s and 1970s," Lusardi told AP News. "Some were so preserved, they could fly again. [Now] when they're removed, the planes look like Swiss cheese. [Quagga mussels are] literally burning holes in them."

Tamara Thomson, a state marine archaeologist from Wisconsin, further describes the severity of the situation, stating: "Every shipwreck in the lower Great Lakes is covered with Quagga mussels. The mussels have completely taken over the wrecks, making it difficult to even identify the original structure of the ships. The sheer number of mussels and their weight pose a significant threat to the stability of the shipwrecks, further increasing the urgency to salvage these historical artifacts."

So far, ideas to manage quagga mussels in the Great Lakes include treating them with toxic chemicals, covering them with tarps to restrict water flow and starve them of oxygen and food, introducing predators, and adding carbon dioxide to the water to suffocate them.

Unfortunately, nothing looks promising. "The only way they will disappear from a lake as large as Lake Michigan is through some disease, or possibly an introduced predator," Dr. Harvey Bootsma, a professor at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee's School of Freshwater Sciences, told AP News.

Neither of those options will happen overnight, if ever, which leaves archaeologists and history buffs alike scrambling. Unfortunately, short of raising all of the shipwrecks and planes from the water for on-land preservation, the only thing archaeologists can do at the moment is document as much information about the wrecks as possible, preserving the knowledge of them if not the actual remains.

READ MORE: 33,000+ Invasive Lake Trout Successfully Removed In Montana Fishing Tournament