If you've noticed more plastic trash than usual on your last trip to a national park, you aren't imagining things a new report suggests. The 5 Gyres Institute, founded to investigate plastic pollution in the world's oceans, just released the results of TrashBlitz, a community-based project, utilizing over 600 volunteers in 44 states, who scoured various national parks and federal lands to not only pick up garbage, but to identify and catalog it according to brand.

The volunteers hit notable national parks like Glacier, Yosemite, and Crater Lakes, but they also picked up trash in national forests and monuments across the country too. Then, they used the TrashBlitz app to catalog what was found. The volunteers tagged 14,237 pieces of trash from the parks, which have since been broken down into categories to see what brands and materials are the biggest offenders.

According to the Gyres report, 81 percent of the trash found on park and federal lands was plastic. And 45 percent of it was related, in some way, to single-use food packaging. The institute recorded hundreds of cups, straws, lids, and utensils. Unsurprisingly, most of this trash was found near campsites and visitor centers.

The institute was then able to categorize the trash by individual items. Cigarette butts made up the most frequent item picked up, followed by wrappers, plastic bottles, bottle caps, textiles, metal bottles, cans, cups, straws, lids, and wipes. Oddly enough, their research shows that textiles account for the fifth-greatest amount of trash found in national parks. When they broke things down by brand, Camel and Marlboro were the top two brands found. After that it's a string of popular brands like Nestle, Coca-Cola, Nature Valley, Gatorade, Pepsi, Crystal Geyser, Parliament, and Kirkland.

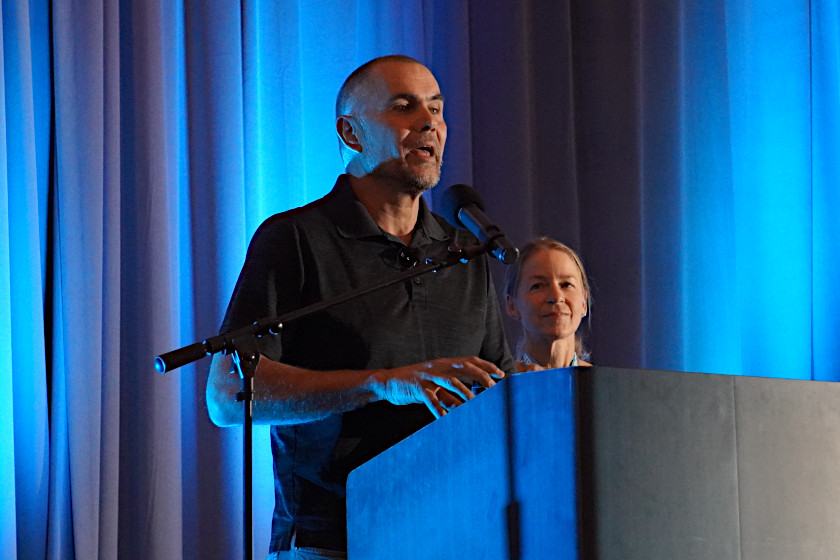

While 5 Gyres reports that the study is limited, in that the results are reliant on self-reported data of volunteers, the results come as no surprise to the institute's Co-Founders Marcus Eriksen and Anna Cummins, a couple who have devoted more than a decade to researching plastic pollution in the world's oceans.

Recognizing a Plastic Problem

5 Gyres Institute Co-Founders Marcus Eriksen and Anna Cummins present their findings at the Outdoor Media Summit - Photo by Travis Smola

The couple presented their findings from the national parks clean-up in a keynote speech at the Outdoor Media Summit in Lake Tahoe last week. The couple have dramatically different backgrounds, but both came to love the outdoors, and both realized plastics were a serious problem through their own experiences. For Cummins, who grew up loving the ocean, and studied marine conservation and coastal watershed management, the realization plastic was a huge problem came while she was taking her open-water scuba certification dive off Monterey Bay, California.

"The visibility was amazing. I was 30-feet down and watching kelp, looking at a playful harbor seal nipping at my finds, and all of a sudden, I couldn't breathe," Cummins said. "I resisted the impulse to bolt to the surface. The dive instructor came over, we shared air, we went up to the surface, and he identified the problem. A tiny piece of plastic film had gotten stuck in my regulator."

That dive happened in 2000. For Cummins, the frightening experience was the perfect metaphor for the problems plastic pollution was causing in the world's oceans.

"Our oceans are literally choking on plastic pollution," she added.

Eriksen, who holds a doctorate from the University of Southern California, describes himself as the total opposite of Cummins. He grew up in the deep south catching snakes and alligators for fun as a child. Eventually, he was called to serve and became a Marine. He was sent overseas during the first Gulf War. While most Americans watched the drama of the burning oil fields in Kuwait on the evening news, Erickson had a front-row seat to "Hell on Earth."

"I remember sitting in a hole in the stand with another marine next to me, we'd dug this hole, and we're sitting there looking at the burning wells, it's Armageddon, and we're laughing because we're hatching this plan. If we survive this war, let's build a raft, like Tom Sawyer and Huck Finn, and let's raft the Mississippi River," Eriksen said.

He followed through with the plan 13 years later, albeit solo because he couldn't relocate the Marine he'd shared the foxhole with that day. Still, the journey down America's largest river took him five months and it changed the course of Eriksen's life.

"In those 13 years of time, I'd kind of lost sight of myself and the goodness of people," Eriksen said, adding that while rafting the Mississippi River, "People fed me, gave me clothing, fixed my raft. And my connection to nature, my connection to the river, became so deep that when I saw trash, it hurt me personally."

Because he enjoyed rafting the Mississippi so much, he decided his next adventure would be to take a boat across the Pacific Ocean to Hawaii. It was a secondary question he added into his marriage proposal to Cummins. Marcus and his friend then took 15,000 plastic bottles, some old fishing nets, and a small aircraft fuselage, and tied it all together to make a boat. They were towed 60 miles offshore from Los Angeles and from there sailed to Hawaii. Eriksen had thought the journey would take six weeks—at most. It took thirteen, and he lost 20 pounds in the process. During the journey, they sailed through a huge garbage patch and brought a lot of attention to the problems of plastic in the ocean.

The key moment on that journey came when they caught a small fish for dinner. When they cut it open, they found the fish was full of bits of plastic. Images of the fish affected by plastic pollution immediately went viral. After that, 5 Gyres started exploring the problem in other oceans. Their travels took them to the North and South Pacific, the North and South Atlantic, and the Indian Oceans. All five gyres, which are systems of rotating currents, had accumulated a huge amount of plastic pollution. In the South Sargasso Sea, they found tons of plastic amid the famous Sargassum grass, a free-floating seaweed. In a moment they captured on video, they rescued a triggerfish found trapped in a plastic bucket. They suspect the fish had spent its entire life trapped in the human-made waste. After that, they expanded their research to the Arctic Ocean.

"In the Arctic we were surprised to find lots of fishing gear, but also a Snicker's bar wrapper frozen into an iceberg," Eriksen said.

Bottle of water from Lake Erie contaminated by plastic pollution. Photo by Travis Smola

The institute quickly realized it needed to make more people aware of the problem. That meant expanding its efforts beyond the oceans since many people do not live along ocean coastlines. Its research efforts focused on the Great Lakes next, where things became even more eye-opening.

"What we found in Lake Erie was more plastic by count than any we had seen in the oceans," Cummins said. "And we were puzzled by this, until we went to CVS and figured out the source. The source was plastic microbeads from personal care products."

That includes shampoo, toothpaste, and other products commonly found in a pharmacy. This discovery, combined with more research after the fact ultimately led to other organizations doing their own investigations into microbeads. Eventually, their work led to the Microbead-Free Waters Act of 2015, effectively prohibiting the manufacturing of and use of plastic microbeads in cosmetics and toothpaste products. At the end of the day, the couple says legislation is the only way to combat the problems caused by plastic pollution.

Combating Plastic Pollution in Our National Parks

Travis Smola

Right now, 5 Gyres says the best way to combat the problem of pollution in our national parks is to eliminate it from being available there completely. And, according to Eriksen and Cummins, the best way to do that is to make plastic products unavailable in those places. According to a press release, the National Parks Service (NPS) began phasing out sales of single-use plastic water bottles around 2011. At least 20 national parks stopped selling water bottles. The Trump administration reversed this policy in 2017. Now 5 Gyres, and groups like Plastic-Free Parks, are working to reinstate it.

More than that, they want to see the Reducing Plastic Waste in National Parks Act passed and codified so later administrations cannot modify it. This legislation would effectively direct the NPS to create a program to reduce the use of plastic products. It would effectively ban the sales and distribution of single-use straws, bottles, and packaging in national parks. In its report, 5 Gyres recommends parks increase access to water and beverage refilling stations, implement deposit returns for beverage containers, and start implementing reusable straws, cups, and utensils inside the parks, a move they admit might lead to the need for expanded dishwashing capabilities.

Plastic-free may be the wave of the future for our parks anyway. Cummins noted in her speech at the media summit that the Department of the Interior (DOI) already wants to phase out single-use plastics. She's frustrated because the DOI put that plan on a 10-year timeline for implementation.

"Come on, you could put someone on Mars faster than that," Cummins said. "So, we've got to elevate that timeline."

Who Owns Trash?

Jeff Greenberg via Getty Images

That's the bigger question Cummins and Eriksen have been asking for a while now. During his presentation, Eriksen showed several ads and articles from Life magazine back in 1955. The ads tout how simply throwing away plates and utensils cut down on household chores, making life easier.

"That began that throw-away culture. Just think about it, before that, we were a culture of conservation," Eriksen said. "Think of it, your great grandparents were probably still washing plastic bags. Because for them, growing up in the depression, around World War II, you didn't throw things away. Things were precious, materials were valuable. We had to learn to throw things away, to drink a bottle of water and throw it away."

The couple concede that many products change hands multiple times before ending up as trash. But for them it's a broader question of ownership when the product has reached the end of its life cycle and ends up someplace it shouldn't be. That's why they are recording the different brands that are being found the most often.

"Is it our city's responsibility to deal with mixed and dirty recyclables?" Cummins asks. "Of course, we as consumers, as much as I don't like that word, do bear responsibility to put things in their proper place, but whose responsibility is it to deal with these things when they slip through the system?"

It's an interesting question, albeit one with unclear answers at this point. However, for Cummins and Eriksen, it all comes back to their pushes for legislation to combat the use of single-use plastics in the first place. When they discovered the microbead problem in Lake Erie, they took their concerns and the published results of their study to some of the leading manufacturers of those products. The owners told them that until they could prove the pollution was coming from their beads, they needed to do more research. Which is what they did, and what eventually led to more groups backing them, and the passage of the Microbeads in Water Act. They're hoping this new data from the national parks waste research will drive new legislation to combat the problem there.

"Now we have some data to drive solutions," Cummins said.

There has been growing concern about the long-term effects of plastic on humans for a while now from organizations other than 5 Gyres. One of the more disturbing trends is just how much plastic is being found in the human body. Cummins and Eriksen knew they wanted to start a family one day. Knowing what they did about plastics, Cummins had a blood test done to check what was in her body.

"We looked for PCBs, DDT, PFCs, and flame retardants in my blood. We found all four contaminants present," Cummins said.

She noted that was simply her base level of chemicals. At this point, many scientists do not know the long-term adverse effects from having plastics in our system. Once again, it comes down to doing more research. I also raised the question of ownership again with 5 Gyres when the problem goes beyond polluting nature.

"There are so many big questions and we come back to the question of ownership," Cummins said. "Whose responsibility is it to protect us from these chemicals?"

For now, it seems we are only seeing the tip of the iceberg when it comes to plastics in our environment. To read the full report on plastics in our national parks, visit the 5 Gyres website. Go to trashblitz.org for more information on its research efforts, to download the app, or to participate in collecting and cataloging trash.

For more outdoor content from Travis Smola, be sure to follow him on Twitter and Instagram For original videos, check out his Geocaching and Outdoors with Travis YouTube channels.