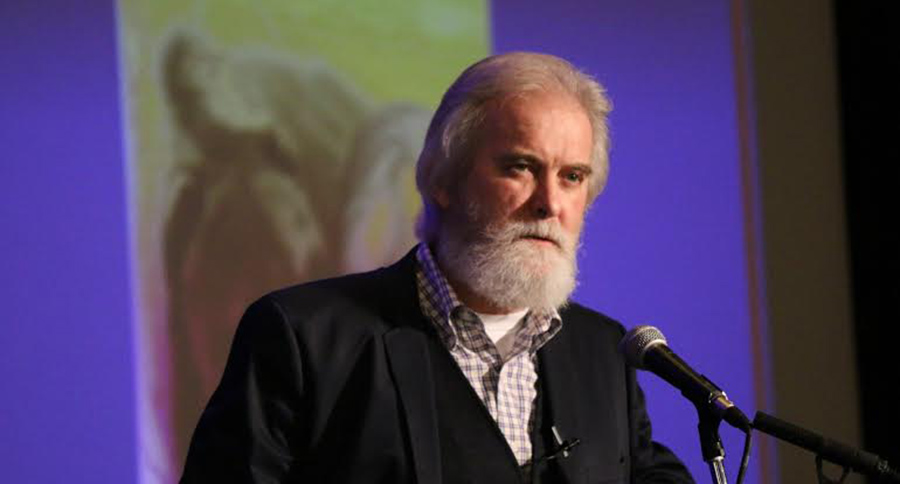

Shane Mahoney has an important message that those who care about wildlife need to hear. Here he continues his advocacy for wild creatures as well as for hunters.

We continue our wide ranging interview with noted wildlife conservationist Shane Mahoney. We pick up where we left off following our first and second installments of our chat with Shane (see the first installment here and see the second installment here).

He talks about conservation funding and where the dollars come from, in contrast with where he thinks they need to come from. Expanding the circle, so to speak.

He also talks about how we, as hunters, anglers, outdoorsmen and women, need to show the best of ourselves, and how we can help more people support what we do, whether they do it themselves or not.

DAVID SMITH: You mentioned the wildlife photographer, and that brings to mind some conversations I've had with anti-hunters, and one of the things that they often say is that photo-tourism is a greater funding source than hunting. And I always say why does it have to be one or the other? Why can't it be both supporting conservation and wildlife management? But I don't believe that photo-tourism alone would foot the bill, whereas with hunting I think that sportsmen, with their dollars and their efforts, they could foot the bill. But why does it have to be either/or? It should be everything.

SHANE MAHONEY: Well, I totally agree that it should be everything. I disagree a little that hunters and anglers could do it all themselves. There is a limit on that amount of activity. And let's not leave out the recreational shooters, because they pour a lot of money into conservation through the Pittman-Roberson process. Even though they're primary interest is in shooting, marksmanship, etc.

But what I will say is that we are collectively in the world—and I do a great deal of international work now—we are collectively in this world, running out of money to invest in conservation. And what we need is for everyone to contribute.

So the idea that we should not have photo-tourism or...I mean bird-feeding is a multi-billion dollar activity in the United States. But none of that does necessarily go directly back into conservation, does it? So on the issue for the amount of money, I think we need every community. We need the bird watchers and those who don't wish to hunt. We need people who are opposed to hunting but still have interest in conservation.

And the ultimate test for me is not whether some individual hunts or fishes, or bird watches, or mountain bikes, or kayaks, or is even concerned about hunting, and has fears of it, or disapproves of it. The most important thing to me about a human being is whether they do something for the natural world and for wildlife.

Now, we're not all going to agree on what absolutely the best way is. But there's definitely cases where photo-tourism can help generate jobs and can help build an economy. And there are places where it can't. Maybe not in Canada or the United States, but in Africa and many other regions of the world. There are places where that kind of activity can contribute, and there are places where it can't. Same way with hunting. You know, we can't have hunting everywhere because there are a lot of people living in dense centers, for example, where we simply can't have it.

What we need is to build a community of interest, which is capable of saying, 'Look, I disagree with you on this particular point, but I'll agree with you that your activity is contributing to the conservation of wildlife, that benefits us all.' And there's a huge group of people in this center that we know. We only have about 5% of the United States, of Americans who hunt. So, it's a small percentage. But we also know that there's a very significant majority that support the activity. They don't do it themselves, but they support the activity because they believe in it.

But just imagine if we could all come together. If all of the people who were working on behalf of wildlife, even if we don't agree with some of their positions, if we could all come together to try to convince the world that keeping wildlife with us is the most important thing...I mean, private landowners and public land, we have all kinds of debates and intentions over that. Yet both kinds of land protect and keep wildlife, don't they? And that's the most important thing.

Now I do believe, in addition to this, that talking to people who have concerns about hunting, which includes people who are not dedicated anti-hunting in their views, but they just question it. 'Is it necessary anymore? Is it relevant? I'm just wondering.' We know that the messaging that deals with things like food makes a huge difference to those individuals.

You ask people whether they support certain kinds of hunting and they have different reactions to different "kinds" that are presented. But when you say that somebody is hunting, uses all of the animal as food, we gain a vast majority of support. And it's been like that forever. Why? Because right back to our earlier parts of this conversation, not only does he who gives find it natural, David, not only the hunter who gives or the angler who gives the wild harvest to someone, it is also the recipient who feels that they are a part of something that has been around for a long time.

It's something that they agree with, that they accept, that they find marvelous, acceptable, reasonable—a good thing to be a part of. So that's why I think this emphasis on wild meat is so potentially valuable for building coalitions and maintaining our support in a modern society for recreational hunting and angling.

DAVID SMITH: You called for outdoorsmen to 'show the best of ourselves.' As you're speaking I'm thinking that this could be one way to show the best of ourselves. Giving meat not just to your family and friends, but sharing with the non-hunter, the non-angler, or even with the anti-hunter, to bring them into the circle, so to speak.

SHANE MAHONEY: I absolutely agree. I really believe—and this is why I've started this project [Wild Harvest Initiative]. I've been in this business a long time.

I've spoken as much about the North American Model, to North American sportsmen and women as much as, I think, any human being. I think I can honestly say that. I write about it constantly. I produce films, vignettes, I produce television shows...I don't think anyone has spoken any more about this. And I really, truly believe that we are at a turning point in society where a lot of people are losing connections. Not just with hunting directly, but with people who did hunt. Because, you know, people are getting older, generations are more removed from the farm than ever, or from rural lifestyles than ever. Urbanization is increasing.

And that is only going to increase, David. We cannot stop that process. We cannot turn the clock back. It's not going to happen. So we have to find a way to show the best of ourselves to a modern society. And I think, showing the best of ourselves... Yes we can talk about the jobs we create. Yes we can talk about the economic impact of our activity. But that is abstract, unless somebody is directly affected. If I have a small restaurant in a rural community that manages to survive throughout the year because in hunting season I make money, and I just kind of float along for the rest of the year, then I get that impact. I understand that impact. It affects me personally.

But for a lot of people saying that we create three-quarters of a million jobs, or that we spend these billions on our activities, yes, it reaches some people, but for a lot of people it's very abstract. It's like a news item, you know, that's like 'the government is going to purchase some new fighter jets, and they've gone up by $50 million each,' you know? Some people will get agitated about that, but for a lot of people it washes over them, right? It's just another statistic in a hurricane of statistics that are coming at them every day.

But food is another matter. Food is something that everybody everyday makes choices about, in one way or another. Whether they go to a fast food chain because they don't have time, or they're planning a nice dinner with their family, whatever! Food is something that is, so to speak, in our faces every day of our lives.

And I think the sharing we do in the community, with friends, with the disadvantaged—we have all kinds of programs where hunters give meat to help people who are hungry. And remember, despite the wealth of our two countries we have lots of people in our countries who are hungry every day. I think that these kinds of things are ways to show the best of ourselves.

You know, I imagined an idea for an inner city program. I had some wild game sausage at this event that we were speaking about in Kansas just a couple days ago. And you'd actually be amazed. I got to thinking about the idea of homeless people in our cities. And every city has them. In Canada and the United States. Every city has them. And the people who are disadvantaged, who knows what their histories are? I don't. But they all have one.

But you know, those kinds of sausages, the beef jerky kinds that are easily portable, that are dried and so on. I can see some kind of event where hunters just took large amounts of these sausages, and just walked through streets and just gave these out to the disadvantaged people.

So it doesn't have to be a soup kitchen kind of thing. There are all kinds of ways that we can broaden this out. And they'd feel good and they'd be grateful. And our communities would be better. We will feel great ourselves. Just like those hunters I talked about in traditional hunter gatherer societies who were honored, revered, respected and appreciated, because they gave this. So I think the food issue is enormous.

And the landscape protection issue is becoming bigger as well. More school children in the United States of America know more about the monarch butterfly than they know about the bison. I'm not saying that's good or bad, I'm just saying that it's a reality. I think it's great that they know about this pollinator problem. But the point is that the pollinator problem is beginning to concern everybody, from the hard levels of political office to the largest industries in your country, to the average citizen on the street.

When we have those kinds of connections, when we find issues that link those together, we need to be a part of that process. We need to find our way into that process, because that's what we're looking for.

So we want to portray what hunters stand for and what hunting stands for. We stand for keeping those places wild. We want wildflowers out there, natural, wild, native flora and fauna in place. We love to see that! We don't want that diminished. We know that the system as a whole is necessary to provide the elk and the waterfowl and the deer and so on that's out there.

So this is another area where I think we have to link as hunters and anglers much, much more with the general public, to say, "Look, we're with you on the pollinator issue."

Just like Pheasants Forever and Quail Forever are doing now with the tremendous programs they have there. We are with you, as a society. Yes we want the landscapes to be clean, we want healthy forests so that we have healthy water systems and good filtration systems. We've got to encourage as much organic farming as we can, and as much free range cattle as we can, recognizing that there are limits.

But we should be part of those things that society has already demonstrated that it cares about, if we want hunting and angling to be relevant in the modern world.

Like what you see here? You can read more great articles by David Smith at his facebook page, Stumpjack Outdoors.

NEXT: Should We Trade Rhino Horn to Save the Species?

WATCH

https://rumble.com/embed/u7gve.v3v4d5/