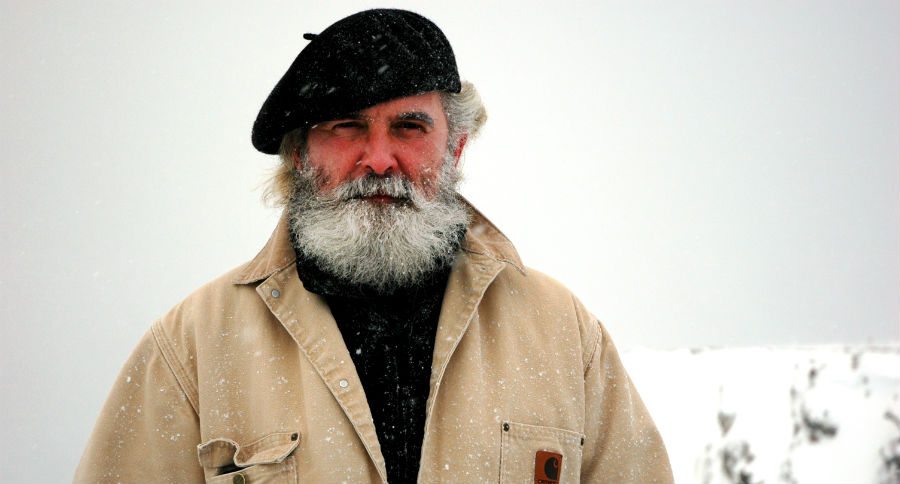

Shane Mahoney concludes his conversation with Wide Open Spaces on wildlife conservation and food systems, closing with his thoughts on selling wild meat.

Celebrated conservationist and leader in the field of wildlife conservation, Shane Mahoney, brings his conversation with us to a close by touching on two very important—and controversial—topics: Changing the hunting narrative in order to reach a broader public, and the selling and marketing of wild game as a food source.

To read the entire exclusive interview with Shane Mahoney, click on the following links:

- Part I: The Wild Harvest Initiative

- Part II: Hunters Sharing Their Harvest

- Part III: Conservation Funding and the Hunter's Image

- Part IV: The Message, History and Anti-Hunting

Mahoney recognizes the challenges of each, but he remains optimistic and open-minded about our ability to discuss and come to some consensus of action on these important issues.

In our last installment Shane was talking about how it is his hope that hunting eventually be seen as an "unextraordinary" activity, a food gathering system no more noteworthy or unusual than, say, gardening or fishing. To get to that point, where, for example, getting a moose every year is no more eyebrow raising than picking a basket of zucchini from your garden, he says we need to redefine the hunting narrative:

SHANE MAHONEY: To get there, we're going to have to redefine the narrative over hunting. And when you try to redefine something, you need mules or landing craft. It can't be you who are promoting it, that ultimately convinces a society. There have to be carriers in society for those ideas.

I use the analogy all the time of a fighter jet. A fighter jet at sea is an amazing instrument. Incredibly complex. Unbelievably maneuverable, able to do all kinds of things. But over the open ocean they will eventually run out of fuel, then this amazing machine will go into the ocean and be destroyed. Unless it can find an aircraft carrier.

And ideas are just like that. If we want to bring this new idea, this new narrative for the hunting world, we need to find those aircraft carriers for our fighter jets, for our ideas. We need mules that we can load, with pack bags, and they'll bring it up the cobblestone streets of society and spread this message for us. And that has to be about something that society is already concerned about.

We know that food is it. The locavore movement, the Omnivore's Dilemma, the Incredible Edible movement in Europe that's just expanding crazily on the continent there. It's amazing what's happening!

They're growing food in cities, that anyone can harvest! They're just planting in abandoned parking lots and other areas, they plant food! We're just being consumed by this at the moment - no pun intended. And we believe that the Wild Harvest Initiative...we need a storyline for the North American Model, for the modern hunter and angler, that's going to effortlessly reach out to a broader public.

I don't think food is the entire answer for what we need to do. As I said, conservation has to be foremost. And there is one thing about that that I will say: We can't just use the word. We've got to be demonstrating it. You know, we have got to be demonstrating that conservation is foremost. And I think we still have a good ways to go to demonstrate that, by doing some bold and innovative things. I can see the day where our hunting organizations provide a percentage of their money every year to help for conservation issues that do not involve hunted species at all.

We should all be doing this. You know, we're not just interested in the animals we hunt. We're interested in sea turtles. We're interested in whales. We're interested in sharks. We're interested in migratory birds, you know, songbirds. We're interested in little toads. We're interested in nature!

This is an easy thing. There are so many easy things for us to do, David, to expand the public's awareness of us, but at the same time make us look like, kind of, just normal citizens who care about their country. And have a particular interest in the natural world. And when did anyone find something offensive in that?

DAVID SMITH: Wow. Let me skip over most of my other questions, because you've answered almost all of them. And I was even going to ask you about women and young urban men, and you answered that too! Let me close with this idea - I don't know if it's gaining ground or if it's just an idea that's floating out there - of marketing and selling wild game meat. My gut tells me that that's a bad idea. What do you think about that?

SHANE MAHONEY: That's a really good question. That is a really good and timely question. You know, the whole approach we took to wildlife conservation was in reaction to the commercial slaughter of wildlife, you know, market hunting. We did that at a time when it was absolutely necessary, and believe me, we did it in the nick of time.

Most Americans and Canadians don't realize that if our countries had had endangered species acts in 1900 whitetail deer, black deer, pronghorn, turkey, elk, every one of them, David, would have been on that list. There's no question about it. They would have met the criteria, they would have been on the list. There would have been no hunting of them, and it would have taken a long, long time to see how that all worked out. It might have destroyed, over time, the entire hunting tradition.

But, we basically set up a system of sustainable harvest and made, in a genius-like turn of mind, we actually made the hunting of animals the major way for recovering them. At a time when you think the logical step would have been to say no more hunting.

Commercial slaughter is what's the problem. And therefore one of the tenets in North American Wildlife Conservation, as recorded by major legislation like the Lacey Act and other things, the law did not allow, by and large, the commercial marketing of dead wildlife. In other words, you can't just take the animal and sell it off. And you don't see wild game easily accessible in markets. If it's raised or farmed or something like this, you can get it. But generally speaking, in Canada and the United States, it's very difficult to sell dead wildlife in terms of food or meat.

But...I've spoken about this model and have written about it, I'm editing a new book on it now with Dr. Valerius Geist, who actually coined the term. So I've written a lot about the tenets of the North American Model, as you know, and I've always supported that.

But it does occur to me as we are trying to think about the modern relevance of hunting, and based on our long conversation now, around this issue of food and wild harvest, and changing the narrative for hunting, and defining its relevance in the modern 21st century America...you know, one has to think about, would there be a way to make that wild protein more available to more people?

If you and I travel to Europe, we can go to almost any restaurant and we can buy wild boar sausage, cheeses, red deer, fish...

DAVID SMITH: Sure, they have them hanging outside in market stalls.

SHANE MAHONEY: Absolutely. And they have managed to implement a system that does not inevitably lead to the slaughter, demise and loss of wildlife. So, come back to North America, at the time when we banned this practice, we didn't have well established enforcement operations, we didn't understand a lot of the biology that was involved with these species, how to manage them successfully.

We didn't have the federal and state institutions that we have today, the wild policies, the many levers, the checks and balances that are in the system. And so I think that your question is a really reasonable one. And before people react and say, "Oh, that would be the end of the world! We can't do that. It's against the North American Model," that kind of thing, I think we should soberly consider this.

And I know there are going to be colleagues who may listen to this and say "I can't believe Shane said that, because he's been such a defender of the model." I'm not saying that we should rush pell-mell into this, David. But I'm trying to think about, okay, yes, some people will be given the meat because you or I know them. They're our family and our friends. And some people may take my advice and try to become a hunter themselves, or find people in their community who do hunt and try to establish a friendship or a rapport or a connection where they can get some food. But there will still be a lot of citizens who may not find a way to access this.

And again, I'm in a grocery store these days, and you wonder. You look around and you see people of different ages and different lifestyles. Single mothers or any mother who's really interested in looking into that meat counter, who really wants to get the best food for her family. Wouldn't it be great if there was some way, without endangering our system, for these individuals to also have access to that meat?

I think the more people who have access to that meat, the more people who benefit from it, and the more people who appreciate it, the more likely we're going to develop a society that has more concern about the fate of the animals that provide that to them.

I don't know... Enforcement officers and people involved with the enforcement side of conservation, will be far better suited to understand and appraise the risks and benefits maybe. But I really think we ought to have this dialogue. I think the time has come for us to talk about this.

And maybe it's a bad idea. Maybe when we examine it, it's a bad idea.

Maybe we should experiment with it in a certain place, in a certain circumstance. Maybe in a place where we have a super abundance of whitetail deer or Canada geese or snow geese, you know. Maybe it could be part of some kind of experimental approach, to kill two birds, so to speak, with one stone. We help reduce an overpopulation of wildlife and at the same time we find a way, because it's a restricted program, to really closely monitor and enforce it so that when that food gets to an outlet we'll know where it's come from, it's not been poached, and brought into that chain illegally.

DAVID SMITH: I hadn't thought of that angle on it. But it does speak to your larger vision of bringing non-hunters, non-anglers into the fold, so to speak. I don't know what the answer is, but that certainly is a twist on it that I had not thought of before.

SHANE MAHONEY: Well, you know we had that experiment recently, with the fast food store. I think it was Arby's that has venison sandwiches. That was farmed venison I'm sure. But the point is that the demand for it was incredible. So you see this goes back to the 'mystique of the wild'. But the fact that this was venison immediately attracted people.

My philosophies about all of this are relatively simple. I work for the wild others of this planet. That's my life, and I will work for that until the day I die. I'm not afraid to say that I'm in love with them. I've got no concerns about saying that I love my dogs or my pets. I absolutely do. I love them like family members. That's what motivates me to care for wild animals.

I've spent most of my life in close proximity to wild animals in ways that most people never have, as a research biologist for 25 years. I'm in favor of any system that keeps them with us. Any system that keeps them with us.

I believe that hunting and angling are major forces in developing people who care, who have an incentive to keep those creatures with us, who give of their time and their money, their energy to do this. And I want to expand that base. We need more people caring about conservation. We need more people, not less, caring about wildlife. And if finding a way to give them this wild food is a way to help bring them into that movement and into this community, then I think we should try to find a way to do it.

If the assumption is wrong, if the premise is wrong, or if it's going to hurt wildlife in any way, obviously, we should not. But there certainly are places where, like South Africa, where the whole idea of having wild game, wildlife, as a food source has resulted in a major conservation success in that country. All I'm saying is that there are examples around the world where this has benefited wildlife.

And a further point on this - and I'm really glad you asked that question - is, wildlife is a public trust resource. It belongs to every citizen. And to no citizen, in the sense that they don't own it themselves, right? It is held in trust by the government. So we have special access to it, to actually take it. In other words, we don't just watch it, we actually hunt and fish, and we harvest, kill, butcher and consume those animals. But only we who are legal and are licensed to do it, do that. And that's fair enough. We make the extra effort, and we want to be in the activity, we enjoy the activity. It gives us so many things.

We should be finding ways to make sure that the public has access to it in as many ways as possible. If that means they want to bird watch, they want to kayak, they want to camp out under the stars, if they want to see wildlife come into a waterhole in Africa, whatever it is. We want to be trying to, in North America, we want to give the benefits of that as much as possible to as many people.

And I really believe that we know that we have some wildlife species, deer and the two geese species that I mentioned for sure, where we could have heavier harvests, and right now the incentive is not necessarily there for those heavier harvests. They may not be possible in urban areas or suburban areas.

Maybe we should look at an experiment where somebody tries this. They harvest those excess animals, humanely, they make sure the meat is inspected and clean, that all of those health and safety safeguards are there. And then we try it, as a small market, and see if it can work. And if it can work, then we can think more widely about whether we want to do this.

Now I'm sure for a lot of people even to think about going down that slippery road is a slippery slope. And I think there's a lot of logic in that argument. So I really try to keep an open mind.

But maybe it's because we're on our way to 9-billion people. We're on our way to a drastically changed world in a very short period of time. The struggle to keep wildlife with us is getting harder and harder. We need more money. We need more supporters, We need more good businesses, more politicians, more doctors, more lawyers, more truck drivers, more farmers, more bank clerks, more service industry people, more mechanics.

You know, we can't leave this problem to just a handful of fanatics like us. It won't work. And so anything that has the possibility of broadening the base of support and engagement, I think it's something that we should be mature enough to at least talk about.

Like what you see here? You can read more great articles by David Smith at his facebook page, Stumpjack Outdoors.

NEXT: Ruffed Grouse Biologist Mentors New Hunters for Future of Conservation