Where is the "world's oldest forest"? Just down the road, it turns out, from what was previously thought to be the oldest network of forest specimen fossils, in New York.

Researchers recently found evidence of a forest 2 million years older than the famous Gilboa fossil forest, which was discovered a century ago in an old quarry in nearby Cairo, New York. Charles Ver Straeten, curator of sedimentary rocks at the New York State Museum, was walking through the new quarry site with colleagues Linda Van Aller Hernick and Frank Mannolini to scout for a potential field trip when he noticed a pattern in the stone underfoot.

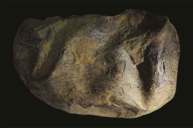

The three weren't strangers to the site, as it had been used for decades by paleobotanists for research, but this trip turned up something different. Ver Straeten identified wandering gutters in the stone, which he traced back to a single point. Suddenly, it dawned on him what he was looking at: the roots of an ancient and very large tree, at a time when forests were still new in the world, according to Binghamton University. This kicked off a large research project in which researchers traced the root impressions to map out the network of trees in what researchers have declared to be the world's oldest forest.

Photo Courtesy of Binghamton University

The trees that once thrived on the fossil site, near the Catskill Mountain range, stood tall when dinosaur footprints were being made in the earth. The evidence left behind offers researchers a better understanding of the planet's biodiversity millions of years ago. The Cairo fossil forest site, which researchers estimate dates back 387 million years, not only predates the Gilboa forest but also the ancient forests of the Amazon rainforest and the Yakushima forest in Japan. What's unique about the upstate New York sites—Cairo and Gilboa—is that the fossils there showcase the root systems of individual trees within the ancient soil. Root structures give scientists insight into the behavior of forest ecology at that time.

"Our primary interest is in the evolutionary history of plants: how plant forms came about, how plants actually develop, how they structure themselves. And then, of course, we're quite interested in knowing how plants actually interacted with each other and with other aspects of their ancient environment," said William Stein, emeritus professor of biological sciences at Binghamton. "Plants are fundamental to understanding ecosystems today, and they are certainly fundamental to understanding the past."

This discovery is huge in the world of paleobotany, which is the study of ancient plant life. So far, researchers have determined that the ancient trees in the Cairo forest reproduced via spores, similar to modern-day fungi and ferns, and not through seeds the way modern trees do.

Getty Images, AvnerOferPhotography | The ancient forest in Yakushima, Japan.

For folks yearning to know more, the Gilboa Historical Society has released a book titled "The Catskill Fossil Forest," co-authored by Stein, Van Aller Hernick and Mannolini. It traces the history of the ancient forest from its initial discovery in the 1800s through the construction of the Schoharie Dam and current research in Gilboa, Conesville and Cairo.

"In our book, we explain that both (the Cairo and Gilboa) sites and the one at Conesville, somewhat younger yet, likely record different aspects of essentially the same forest lasting several millions of years in the Catskill region," Stein said. "These sites together currently record the best evidence worldwide of forests during this time period."

Researchers believe that by studying the ancient Catskills, they can glean some insight into the current climate change conditions.

"It is no exaggeration to say that event was unique in Earth's history and of highest importance to understanding how Earth's systems interconnect," Stein said. "Devonian 'afforestation' is essentially the same process but in reverse to what's happening today: deforestation, burning fossil fuels, with related increase in climate mean temperature."

READ MORE: How Pine Trees Can Help You Survive In the Woods